But I wonder if they also steal dignity there? In El Paso? I have to ask the teacher what dignity really is, what it looks like. Does dignity look different in every place you go?

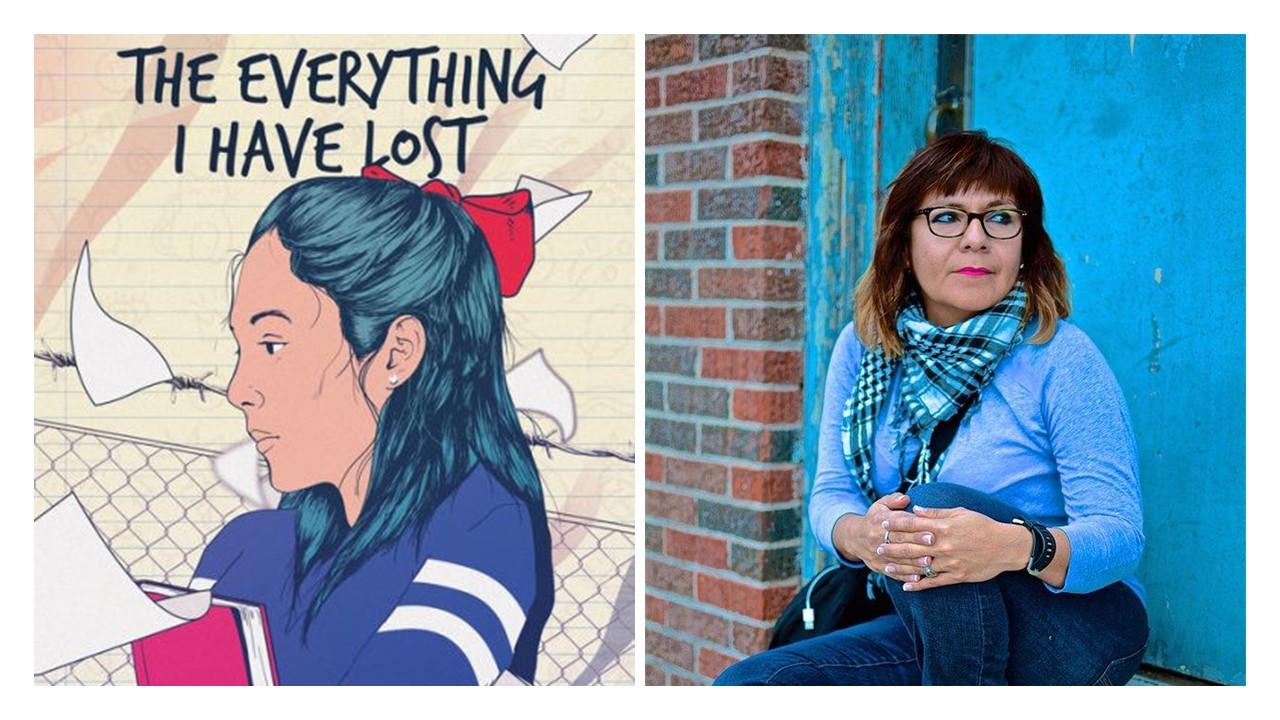

Excerpt from The Everything I Have Lost by Sylvia Zéleny. Copyright © 2019 by Sylvia Zéleny. Excerpted with permission from Cinco Puntos Press.

January 30th

A cherry-flavored lipstick.

50 pesos.

Two boxes of Chiclets: mint and watermelon.

A Hello Kitty wallet.

A keychain that said, I <3 Texas that Tía gave me.

My old diary with three blank pages.

Everything. Everything that I had in my purse. Everything that was left in the car.

The car that was stolen.

We walked out of the movie theater and it was gone. Mamá asked Papá if he had forgotten where it was parked. We looked everywhere. But the car was nowhere to be found.

Mamá cried, Our car, our car. Willy didn’t say anything, he kept quiet. He just looked at us like he was trying to understand, but not really. Willy doesn’t really talk that much. He’s like Papá. Quiet like a stone in the middle of nowhere. Papá, as always, he was just mad on the inside. But on the outside, well, you can never tell what he’s like. Except when he drinks beer. He is all smiles when he drinks beer.

Papá took his phone and called someone. Papá and his commands, do this, do that. He said, Pick us up at the movie theatre. No, the car didn’t break down. The car is gone. Yes, gone.

I am not surprised. This is becoming more and more common here. Juárez is becoming the city that steals cars, girls, and our dignity, my teacher says. I wonder what dignity looks like. All I can think about is my purse, my lipstick, the pesos, my gum, my diary, my I <3 Texas keychain. From now on we will have to wake up earlier, we will have to start keeping coins in our pockets, we will have to take the bus, I hate the bus. It’s embarrassing to take the bus.

It sucks, it really really really sucks. We were just getting used to it. I look out the window, I hate this city, I don’t know why we came to live here, I still can’t get used to it. All I can think of is my things.

February 2nd

Mamá gave me this new notebook with the words Just Write on the cover. So: new diary, new writing, same girl. At first, I wanted to rewrite everything I could remember, but then I thought, what’s the point? I will just share some basics and move on.

I was born in El Paso, right over there—>. I can see it from here, I see some buildings from my window. I lived there for like a second, then we moved and moved and moved. I wish I could live in El Paso, people say it is much better. I am sure it is, I am sure it is way better than this or any of the cities Dad has made us live in. In the last years we’ve moved a lot. Believe me, I can tell you anything about Sinaloa, Sonora, Nuevo León and Tamaulipas. Tamaulipas, isn’t that a very nice word? In the news they say that in Tamaulipas people steal cars and girls. And dignities, my teacher would add.

But I wonder if they also steal dignity there? In El Paso? I have to ask the teacher what dignity really is, what it looks like. Does dignity look different in every place you go?

February 23rd

Mamá took me to the dentist today. I hate the dentist. The place was packed, as if all the kids in the world had cavities at the same time: a plague of plaque! We sat and waited. Mamá read her book and I grabbed a magazine.

I read a phrase in it that I liked. I wrote it down so I wouldn’t forget: Kids and crazy people are allowed to speak the truth and to say the opposite at the same time.

In this diary, I’m going to speak the truth and also say the opposite—

at

the

same

time!

February 27th

I show some of my classmates my new diary. They say that no one writes in diaries anymore. They say that it’s just for bored old ladies. I’m not bored or old. I write just because. They just don’t get it, except for Tere. She says that writing in a diary must be like keeping a slice of everything.

Slice,

slice,

slice.

Tere has never asked me to show her the inside of my diary. She just asks me what I write about. I go, Sometimes I write about what I see, do, hear, eat, drink, and smell. I write about whatever I want. Sometimes I observe everything that happens in the day and wait till nighttime to write it down, detail by tiny detail, by tiny detail, by…

She smiles. I tell her that sometimes my day is wasted and flat and I think there’s nothing to write in my diary, but then I end up writing more than ever. Tere nods. Tere gets it.

I think there are stories that are not planned, they just come out. They come through your fingers at lightning speed and all of a sudden you can’t stop writing. It’s like someone dictated paragraphs of your life to you, and you are just trying to keep up.

I wonder what would happen if I didn’t obey that voice and didn’t write. Would paragraphs haunt me in my sleep? I don’t want paragraphs to haunt me, so I follow the voice. I follow my voice. When Mamá sees me writing she says, You remind me of me when I was a kid. Only she didn’t write, she drew. Mamá is an artist, she draws, paints, takes photos, she sometimes teaches art to rich ladies and rich kids.

Tía told me once that Mamá could’ve been a famous artist. She can’t be one no more? I asked her. Tía looked at me and said, Not with that father of yours. I don’t know what she means, but it feels like one of those better-not-ask things.

Anyway, there are also things that you swear you will never write about, and you end up writing down each and every one. It’s like something you can’t avoid. You just write. Yes, there are you-better-write-about-it things. Like Tere, I better write about Tere.

March 9th

I have always been really bad at school, maybe because we moved a lot, and I was always the new girl. Or perhaps our moving has nothing to do with it, and I just suck at school. Who knows? Anyway, when I started going to school here in Juárez, the school year had already started, and everybody knew each other. And worse, everybody knew what was happening on the board. I would see letters or numbers, or letters AND numbers, and didn’t understand a thing.

Two weeks after my arrival, examinations started. Mamá tried to convince them not to test me, not yet, but our teacher and the principal said that was the only way to see how I was doing. I asked, What if I fail, will you send me back to fifth grade? They said no, but I didn’t believe them.

I was freaking out. The test came, and I did not know what to do. The first section was math. I was just as blank as the paper in front of me. Then this girl right next to me showed me her test, pointed out the answers with her pencil. Are you sure? I whispered. She nodded. That girl was Tere.

I’m gonna be honest, I did copy many things from her test, but some others I answered on my own, maybe seeing her stuff made me remember this and that. She gave me confidence. She still does, and that is why she is my best friend.

Tere was once the new girl at school, and she too came from another city to live here, so she knew what it felt like to not know a thing about anything.

Sometimes we hang out with the rest of the girls at school, but mostly it is us, only us. We don’t need anybody else. We sit down, share our lunch and talk about our favorite TV shows and our favorite singers and about the other girls and clothes and shoes

and…

and…

and…

March 19th

This is Willy, he is six, and this is Julia, she is twelve, Mamá says to the nurse who will give us shots, and…

I interrupt Mamá and correct her: I am almost thirteen. Thirteen.

I can see Mamá and the nurse sharing a look like they want to laugh at me, but they don’t dare. The nurse says, Thirteen, wow, you are almost a teenager. Then she takes Willy and sits him on the table, she cleans his arm and says, This won’t hurt a bit. Willy looks at Mamá, like he’s begging for mercy. It is OK, Mamá says, you will get candy later.

Then it is my turn. The nurse says, Well, since you are ALMOST thirteen, this will be your last shot ever. I feel important. I ask Mamá if this is true. Yes, she says. This is your last shot ever. The nurse cleans my arm and then she asks, So tell me, now that you are almost thirteen, do you have a boyfriend and everything? I shake my head. Are you sure? I wanna say, Believe me, lady, if I had a boyfriend everyone would know, but instead, I shake my head and smile. She gives me the shot and my smile disappears. It sucks to be almost thirteen, but still stuck at twelve, cause you gotta look old and yelling or crying is out of the question.

March 30th

Papá has a new job and he’s going to make A LOT of money, that’s what he said today at dinner. I went with el Gringo, he told Mamá, I’m in. I will get a car and everything. Mamá didn’t reply. Papá asked Willy and me if we were happy that he had a job. We both said yes. I am the happiest because having a car means we won’t have to ride the bus again.

I really really really hate the bus. It’s always so crowded, and people who ride it have big bags and luggage and many of them stink. Mom says that it is because they are going to El Paso or coming from El Paso and they walk to and from the bridge. And what’s in their bags? I ask her. Treasures, she says. Mom says that people bring treasures for their families here to Juárez, or they take treasures to their families in El Paso. But what kind of treasures? I want to know. Mom first shrugs, then says, Think of what your auntie brings you when she visits us. I close my eyes and I see:

Chocolates

Peanut butter

Bread, lots of bread, the one with nuts

Boxes and boxes of macaroni and cheese

Chips in a can

Tía and Bis come every other weekend to visit from El Paso. They bring stuff for all of us: food, shoes, toys, stickers. And when they leave they take tortillas, bread, chile colorado, and cheese that they buy from the market downtown. I guess there’s no tortillas, bread or cheese over there.

Anyway, once Papá gets this other car, we won’t have to ride in the bus squished by bags that smell like soap or chorizo. If everything goes well, he will buy one for Mom by Christmas. Papá says that things are looking good for him, and luckily we won’t have to move again in a very long time. Mamá insists, We should try to move to El Paso, maybe you can get a job there. Papá says that maybe it’s not a bad idea to move to El Paso, but he doesn’t need a job because he works with el Gringo.

Mamá makes a face, it’s like she doesn’t like this el Gringo. I can’t help it. I ask, Who is el Gringo?

Mamá just stares at Papá. She has her see-I-told-you-so face. Then she insists, We could live in El Paso. If you get your visa, there would be no need to work for this guy.

Dad says nothing.

Mamá was born in El Paso, Willy and me were also born there too. Many kids in Juárez are born there, then brought here. Papá was born in Mexico. Bis doesn’t like Papá all that much. She says he is a bit of an ass.

I like it when adults say words like ass, balls, shit or the F-word. Especially the F-word. One day I will write the F-word with bold capital letters. I think the F-word is kinda cool. And pinche, I love pinche. I never use pinche.

Papá uses that word a lot. He uses it the way other people use salt or sugar. If he’s mad, he uses it a lot. If he’s not mad, he uses it just sometimes. Pinche this, pinche that.

April 1st

Mamá doesn’t let us go outside. We don’t do it, but we always want to, especially now that we’re on summer vacation. No, no, Mamá says, the street is not a safe place. Come on, I tell her, we will just be right outside the house.

Mamá: No.

I try again, this time I use my brother. Willy REALLY wants to play outside, Mamá. Come on.

No and no.

She opens the curtain and shows me the street. Do you see anyone playing outside? she asks. She is right. There isn’t anyone playing outside. The only ones playing on the streets from time to time are dogs or cats.

Willy pulls my sleeve and tells me to just go to our backyard. So we do.

He takes one of his Lego figures, and I bring my diary, but Mamá tells me to leave it behind and play with my brother. Our backyard is super small. I don’t even remember when the last time was when I came out. The walls are higher than before. This is a fortress made of concrete and glass, lots of broken glass on top of it all.

After a while, I tell Willy we should just go inside and watch TV.

On TV we watch kids balance on top of walls like the ones in our backyard, like gymnasts. Up they go. We could never do it here, not on our walls, not on anyone else’s walls, because all the walls here have broken glass. All the houses here are concrete fortresses.

It is really no fun to play in a fortress.

Excerpt from The Everything I Have Lost by Sylvia Zéleny. Copyright © 2019 by Sylvia Zéleny. Excerpted with permission from Cinco Puntos Press.

Sylvia Zéleny, a bilingual author from Sonora, Mexico, recently became a US citizen. She has published several short-story collections in her native Mexico, has an MA in Historiography from Instituto de Monterrey / Juárez, and an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Texas at El Paso, where she is currently a visiting writer.