"The prairie chicken, at first glance, does not look like a bird that would inspire artists and poets, much less like a bird that one day would have a national wildlife refuge devoted exclusively to its preservation."

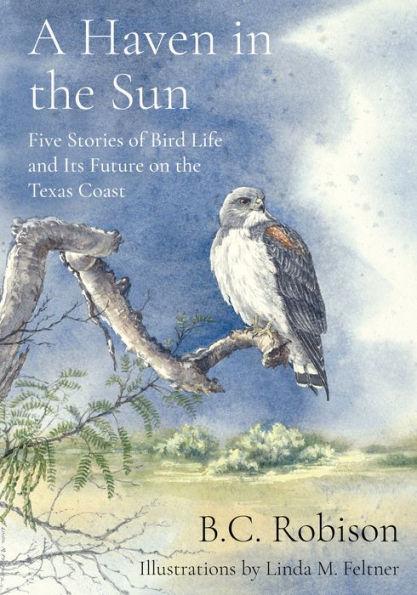

From A Haven in the Sun: Five Stories of Bird Life and Its Future on the Texas Coast by B. C. Robison (illustrated by Linda M. Feltner), published by Texas Tech University Press. Copyright (c) 2020 by B. C. Robison. Used by permission.

Chapter 1

Drums of the Prairie: The Life and Hard Times of Mr. Attwater’s Chicken

The story of Attwater’s Prairie Chicken recounts a journey from a time of abundance to its status today as one of the world’s most endangered animals. It is the story of warnings sounded early and long ignored, of research and action long delayed, of exploitation and indifference fought by scientists and citizens who wanted nothing more than to prevent the ultimate fate that this unique species, or any species, could endure. At the beginning of the twentieth century, this secretive, social grouse of the Texas coastal prairie pecked and strutted through the grass in vast numbers. To the early settlers and explorers, the courtship call of the prairie chicken – the mournful warble that floated at daybreak over the damp grass in springtime – was the music, indeed the soul, of the prairie. In the words of one of the early wildlife scientists to study the bird and its habits, the prairie chicken was an intimate part of the “…colorful and eventful early days in Texas. The prairie hen summons memories; it prompts old timers to recall when the range was free of wire fences and oil derricks, and rich grasses grew waist high.” The bird’s population today (ranging between several dozen and several hundred, depending on the time of year) survives only by the sustained intervention of wildlife and range managers, private landowners, captive breeders, and the Federal government.

The prairie chicken, at first glance, does not look like a bird that would inspire artists and poets, much less like a bird that one day would have a national wildlife refuge devoted exclusively to its preservation. It is a light brown, darkly striped wild grouse that skulks through grass, eating insects, seeds and bits of plants. The prairie chicken doesn’t wander far from where it was hatched, spending its life hiding from danger, feeding, laying eggs in secluded grassy nests, and raising young. It flies for short distances, with bursts of powerful wing beats. The bird doesn’t have a long lifespan, perhaps no more than a year or two, before owls or coyotes or stormy weather kill it. The seasons of its life cannot match the majestic flight of the Whooping Crane, the great, raucous clouds of waterfowl, the menacing verve of the raptors, or the epic migrations of shorebirds. It is a creature of the prairie grass, shy, secretive, elusive.

When it was first discovered, the Texas coastal grouse was standing in the way of a society emerging from its rural past into the modern world. The story of its decline follows the chronicle of not just the rise of modern Texas, but of the disappearing prairie, from the time when great pastures of bluestem, switchgrass, and Indian grass lay among the rivers and woodlands, before the arrival of the plow and the pump jack. The bird’s way of life, its vulnerabilities, its unyielding need for the prairie grass, would not allow it to withstand the assaults that were to come.

In the spring of 1893 an Englishman and former bee-keeper with the improbable name of Henry Philemon Attwater went grouse hunting in the prairie grass of Refugio County, Texas. He shot two adult males there on March 27, and several weeks later he killed an adult female and three chicks in Aransas County, to the south, near the Refugio County line. In November, Attwater shot two more adult females in Aransas County and, in January of the following year, he headed east to Jefferson County, killing a male and female.

At the time there was nothing remarkable about Attwater’s hunting expedition. This Texas bird, along with other grouse species throughout the United States and Canada, was a popular and abundant game bird. The Greater Prairie Chicken, the Ruffed Grouse, the Lesser Prairie Chicken and others ranged widely over the prairies, forests and mountains of North America. Often slaughtered for sport and left to rot in piles, the Texas grouse inhabited the Gulf coastal prairie from southwestern Louisiana to the Rio Grande. Many accounts by early Texas explorers speak of encounters with “prairie fowl.” German naturalist Ferdinand von Roemer wrote of seeing prairie chickens near Stephen F. Austin’s headquarters at San Felipe; John Charles Beales, of the Rio Grande Colony, observed great flocks of them near Copano Bay, in 1834.

Attwater most likely did not realize it at the time, but he and the striped, chicken-like birds that were soon to be named after him were about to enter the annals of American ornithology. Today these specimens of Attwater’s Prairie Chicken reside on Constitution Avenue in Washington D. C., on a broad wooden tray in case number M-16A, on the sixth floor of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History.

But on that spring day, Attwater, a self-taught amateur naturalist who had moved to Texas only a few years earlier, had set out in pursuit of science, not food or sport. He was collecting specimens for Major Charles Emil Bendire, one of the renowned ornithologists of the day. The nineteenth century would not consider Bendire at all unusual, but he would be difficult to imagine today: He was an Army officer who spent his spare time on post studying natural history and collecting biological specimens. Scores of career Army officers of that era, many of them in the medical corps, studied the wildlife of the regions where they were assigned, often making important contributions to scientific literature and collections.

The German-born Bendire spent much of his military career in the West and Pacific Northwest, studying birdlife and collecting eggs. He wrote Life Histories of North American Birds and corresponded with some of the leading naturalists of the time – Joel Allen, Spencer Baird, Thomas Brewer. He also served as honorary curator of the egg collection at the United States National Museum, as the predecessor of the Smithsonian Institution was then known, having donated his extensive collection to it. Bendire’s thrasher (Toxostoma bendirei) bears his name. Field scientists throughout the country considered it an honor to collect specimens for him.

Bendire had been studying the geographic ranges of two closely related species of prairie grouse, or “hens,” as they were then called, that were widely distributed throughout the grasslands of the American Great Plains: Tympanuchus americanus, the prairie hen, and Tympanuchus pallidincintus – the lesser prairie hen. Bendire had received word from friends in the Army that a population of hens inhabited the grassy coastal plains of Texas. Determined to identify this unknown species, he requested specimens from colleagues in the field, Attwater among them. Attwater sent him the birds which he collected in Refugio and Aransas counties in March and April of 1893.

He studied Attwater’s initial specimens and then announced in Forest and Stream in May of that year that he had identified a new species, which he named the southern prairie hen. He observed that the new species was “similar to T. americanus” but slightly smaller than that species and had less feathering on the legs. Granting it the status of a full species, he named it Tympanuchus attwateri, after Attwater.

Bendire, however, changed his mind. When Attwater sent him the specimens that he had collected later that year, he was forced to reconsider his original identification. “Since my preliminary description of this bird…” Bendire wrote in The Auk in April of 1894, “I have examined considerable additional material and am now compelled to consider it as only a well-marked race of T. americanus.” The physical differences between Attwater’s hen and the prairie hen simply were not, in Bendire’s reappraisal, great enough to merit designation as a full species Thus, the southern prairie hen was only a sub-species, a geographic variant of the bird known today as the greater prairie chicken. This taxonomic demotion was to have adverse consequences for the bird seven decades later, when Federal conservation efforts began.

Bendire graciously acknowledged Attwater’s contribution. “All the material received was kindly procured by Mr. H. P. Attwater of Rockport, Aransas Co., Texas,” he wrote, “and generously donated by him to the U.S. National Museum Collection….” Continuing his tribute, Bendire named the bird Tympanuchus americanus attwateri, “as a slight recognition for his trouble in obtaining these specimens.”

In 1931, The American Ornithologists’ Union renamed the prairie hen as the greater prairie chicken, with a new scientific name, T. cupido; this species is designated today as T. cupido pinnatus, after the male’s ear tufts, or pinnae. Tympanuchus cupido attwateri is today the bird which forever bears the name of Bendire’s diligent collector – Attwater’s Prairie Chicken.

Henry Attwater spent his remaining years promoting Texas agriculture and horticulture and in wildlife study and conservation. He was among the first to promote the economic value of bird life to farmers, stockmen and fruit growers. He lectured at county fairs, wrote books and newspaper articles, worked on behalf of legislation protecting wildlife (such as the 1903 Model Game Law, one of the nation’s first legal protections for birds), published in scholarly journals and, always, studied the birds and mammals of Texas.

But among his many pursuits, birds were his passion. H. C. Oberholser, author of The Bird Life of Texas, wrote in Attwater’s obituary, “…perhaps no one in Texas has done more to advance the cause of ornithology in the State than has Henry Philemon Attwater.” Attwater died in Houston on September 25, 1931. He is buried in Hollywood Cemetery, in Houston, next to his wife Lucy Mary Attwater, a simple plaque marking his pine-tree-shaded grave.

Scientists have studied the ways of the world’s 19 species of grouse to an extent rarely matched in other families of birds. This importance to researchers comes as much from the bird’s role in society as from its biology and ecology. Grouse provide hunters several of their most prized game birds, such as the Red Grouse of Scotland. They possess a wide range of mating behaviors that make them an ideal subject for the study of sexual selection, evolution, and sociobiology. And, because of the birds’ need for spacious, narrowly defined habitats, grouse researchers have established much of the foundation of our understanding of wildlife-habitat relationships and landscape ecology. Each species of grouse has adapted to a specific community of plant life, a natural assembly of different plants that feeds it, that provides cover from its enemies, nests for its eggs and shelter for it and its young.

At the time that Attwater was collecting his specimens along the Texas Coast, North America’s twelve species of grouse occupied much of the continent’s arctic and temperate regions north of Mexico, except for portions of the desert southwest and the forests of the American South. Grouse occupy coniferous forests from Alaska to Labrador, the Cascade Range of the Pacific Northwest and throughout the Cascade Range of the Pacific Northwest. They inhabit the hardwood forests of the Eastern Seaboard and regions of sagebrush from Montana to Nevada and Oregon. Ptarmigan inhabit the tundra and northern mountain ranges above the timberline. The prairie grouse – the greater and lesser prairie chicken, and the sharp-tailed grouse – range throughout various regions of the Great Plains, the great expanse of grasslands that spreads across the interior of North America.

All extant grouse throughout the world have declined in population, some severely, others to a lesser degree, as their historic natural habitats have disappeared. The prairie grouse – the greater and lesser prairie chickens and the Sharp-tailed Grouse-- have suffered the worst loss of habitat in numbers and habitat and face the greatest need for recovery efforts. But none of the extant grouse species has been pushed so near the precipice of extinction as Attwater’s Prairie Chicken.

From A Haven in the Sun: Five Stories of Bird Life and Its Future on the Texas Coast by B. C. Robison (illustrated by Linda M. Feltner), published by Texas Tech University Press. Copyright (c) 2020 by B. C. Robison. Used by permission.

B. C. Robison has over twenty years of experience in human health and ecological risk assessment, toxicology, site investigation and remediation, and litigation support. He holds a BA (magna cum laude) in biology from the University of St. Thomas, a Doctor of Veterinary Medicine degree from Texas A&M University College of Veterinary Medicine, and an MA and PhD in biology from Rice University.

Dr. Robison has also served on several advisory committees for the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality to assist the agency in the development of environmental policy, regulations, and guidelines. He is an adjunct associate professor in the Department of Management and Policy Sciences at the University of Texas School of Public Health.

He wrote the “Texas Naturalist” column for the Houston Post for ten years and is the author of Birds of Houston, published by the University of Texas Press.