“He told me no Blacks were allowed to play,” Richardson said. “He left me home. I thought he should have refused to go and forfeited the games. He didn’t. We lost all three games.”

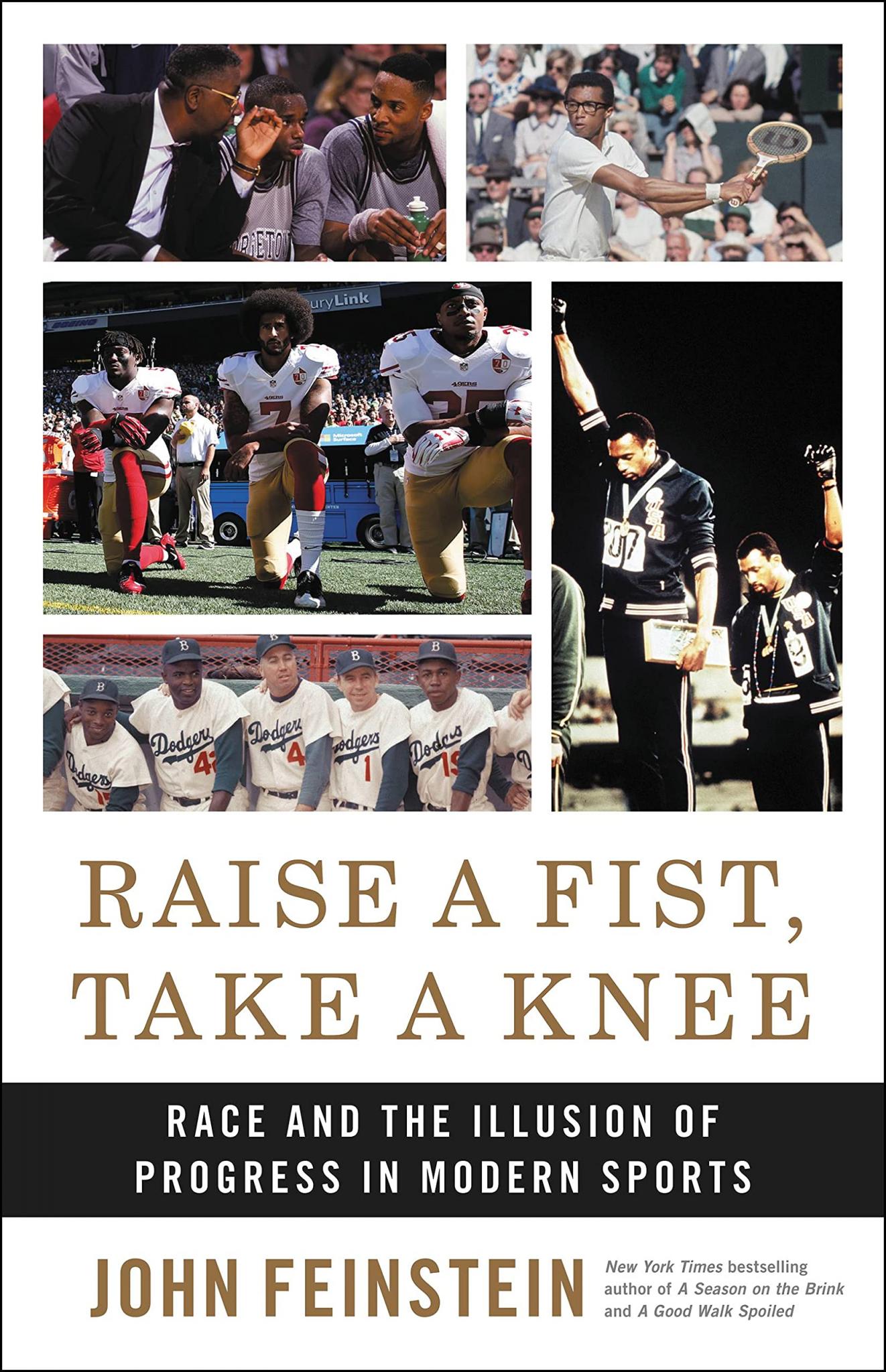

Excerpt from RAISE A FIST, TAKE A KNEE by John Feinstein

Copyright © 2021 by John Feinstein.

Used with permission of Little Brown and Company. New York, NY. All rights reserved.

Richardson was born in December 1941—a few months after John Thompson. He grew up in El Paso, Texas, the second of three children. His father was rarely around, and after his mother died when Nolan was three, he and his siblings moved in with their grandmother, Rose Richardson— who Richardson always affectionately referred to as “Ol’ Mama.”

“It’s impossible to explain how important she was in my life,” Richardson said. “She was very smart and very tough. She never let me feel sorry for myself because of all the racism I faced growing up. She would say, ‘Don’t come back and tell me you couldn’t do something because you were dealing with someone who was racist. All that means is you have to be better—much better—than the next guy.’ “That’s really the way I’ve lived my life. I’ve always taken it for granted that I have to be way better than the next guy if I want to succeed at anything.”

Richardson lived in the El Segundo Barrio of El Paso and could walk from his house across the nearby bridge into Juarez, Mexico. Many of his closest friends were Mexicans and Mexican Americans. In Jim Crow–segregated El Paso, Mexican Americans weren’t subject to Jim Crow laws.

“I had two sets of friends,” he remembered. “I had one group who could go into movie theaters, could go into swimming pools, could walk into any restaurant and get served. I had another group who— like me— couldn’t do any of those things. Those aren’t things you ever forget.”

Richardson was often described in the media as someone who “coached with a chip on his shoulder.”

He laughed at that description. “I didn’t have a chip on my shoulder,” he said. “It was more like a mountain. A boulder wouldn’t be enough to describe it. I grew up hearing the word nigger for as long as I can remember. It was used by people all the time where I lived. I went to a small all-Black school. By small I mean this: the first grade and the second grade were all in one room. There wasn’t enough space to give each grade its own classroom. I understood racism and what it entailed from the time I was very little. But Ol’ Mama wasn’t going to let me use that as an excuse not to succeed.”

Like many kids from financially insecure backgrounds, Richardson used sports to escape. He was a three-sport athlete, excellent in football and basketball but probably best at baseball. After the US Supreme Court outlawed segregation in schools in 1954 with its Brown v. Board of Education decision, he enrolled as a high school freshman at Bowie High School.

He was the only Black kid on the school’s athletic teams. The fact that almost all his teammates were Mexican Americans wasn’t a problem for Richardson, because he had grown up speaking Spanish. If John Thompson was bilingual because he spoke English and profanity, Richardson was truly bilingual.

Richardson was recruited by several schools for baseball and basketball. But low board scores meant he had to spend a year at a junior college in Arizona before transferring back to his hometown to play basketball at what was then Texas Western College.

He arrived at Texas Western in 1960 and played for Harold Davis as a sophomore. Richardson enjoyed playing for Davis, whose style was wide open and who gave him the green light to shoot whenever he had the ball. But the young man soured forever on the coach when Texas Western was invited to play in a three-day tournament at Centenary University in Louisiana.

“He told me no Blacks were allowed to play,” Richardson said. “He left me home. I thought he should have refused to go and forfeited the games. He didn’t. We lost all three games.”

Davis left at the end of the season to work in his family’s thriving oil business. The school hired a thirty-one-year-old high school coach named Don Haskins in his place. Richardson was never thrilled playing for Haskins, largely because the coach liked to play half-court basketball and Richardson like to play up-tempo—as he would prove during his coaching career.

He went from averaging 21 points per game as a sophomore to 13.6 per game as a junior and 10.5 as a senior. But because Haskins left him little choice, he learned to play defense.

Haskins’s way worked. The Miners were 37–13 during Richardson’s junior and senior seasons, making the NCAA Tournament for the first time in school history, in 1963—Richardson’s senior year. Three years after Richardson graduated, they were 28–1 and beat Kentucky in the national championship game, 72–65, in what became college basketball’s most famous game because Texas Western started five Black players against all-white Kentucky.

In later years, Haskins always insisted that he wasn’t trying to make any kind of political statement by starting five Black players. “I was just trying to get the best players possible on the court to try to win the game,” he often said.

It wasn’t quite that simple. According to Rus Bradburd’s excellent biography of Richardson— Forty Minutes of Hell— Texas Western pulled into a hotel in Abilene, the same hotel where Richardson hadn’t been allowed to stay several years earlier during a high school baseball tournament. When the manager told Haskins, ‘No coloreds here,’ the coach took his entire team to another hotel. He did the same thing in Utah at another hotel that would not allow the (then) four Black members of the team to register. Haskins may not have wanted to be cast as some kind of political reformer, but he did know racism when he saw it, and he stood up to it.

Richardson was a father by the time he graduated from college, having married his childhood sweetheart during his junior college year in Arizona. He and his wife, Helen, eventually had three children.

Soon after graduating, he took a job at Bowie High School, his alma mater. He taught English, social studies, history, and physical education. He also coached the JV football, basketball, and baseball teams. All for the princely sum, according to Bradburd, of $4,500.

In 1967, Richardson was drafted by the Dallas Chaparrals of the ABA and went to training camp briefly before a leg injury sent him back home to El Paso. His old job was gone, but he was offered the job of varsity basketball coach.

And so, a Hall of Fame career was launched.

“At that point in time, being a college coach never crossed my mind,” Richardson said. “There weren’t any Black coaches at major colleges. I don’t mean only a few; I mean zero. So why would I be thinking I’d get a chance someday?”

Richardson built an excellent program at Bowie, but, thinking he had no chance ever to get a college job, he resigned at the end of the 1977 season.

=====

John Feinstein is the author of 45 books, including two #1 New York Times bestsellers, A Season on the Brink and A Good Walk Spoiled. Fourteen of his books are young adult mysteries. One of them, Last Shot, won the Edgar Allan Poe Award for mystery writing in the Young Adult category. He is a member of five Halls of Fame and currently contributes to The Washington Post; Golf Digest, Golf World and the Black News Channel. He is also the TV color analyst for UMBC basketball.