"As a writer, it’s the ink that defeats the blank page. For me, it’s amazing how easy a story flows, once I have the starter."

Lone Star Literary Life: The First Line just celebrated its twentieth year in publishing. What are some of your top highlights as a publisher?

David LaBounty: Seeing a copy of The First Line in two major motion pictures (Ruby Sparks and Stranger Than Fiction) was beyond cool. And being interviewed by Scott Simon on NPR’s Weekend Edition wasn’t too shabby. But working with new authors and then watching their careers take off has been the real treat.

On your website, you say the purpose of The First Line, a journal which is published four times a year, “is to jump start the imagination--to help writers break through the block that is the blank page.” And it has a unique hook: writers send in stories and poems that begin with the first line you provide. How did you come up with this idea for a publication?

Right after college, a friend of mine, Jeff Adams, and I came up with an idea to help with our writing that was inspired by a scene from Out of Africa. At the end of each letter we sent (this was many years before email), we would include a sentence that the other person had to use to start a story. We exchanged first lines and stories for several years. Some of the stories were published, some were barely worth reading. It got to the point where we would challenge each other with increasingly difficult sentences, and the fun part was taking the sentence in a direction the other person didn’t think possible.

During this time, I began to realize how few publications there were for new and even established writers. I had an idea to start a literary journal, then picked a graduate program willing to teach me the basics of running a publication. When I got out of school, I knew I needed to stand out, so I went back to our old letter writing exercise. I asked Jeff if he wanted to join, and The First Line was born.

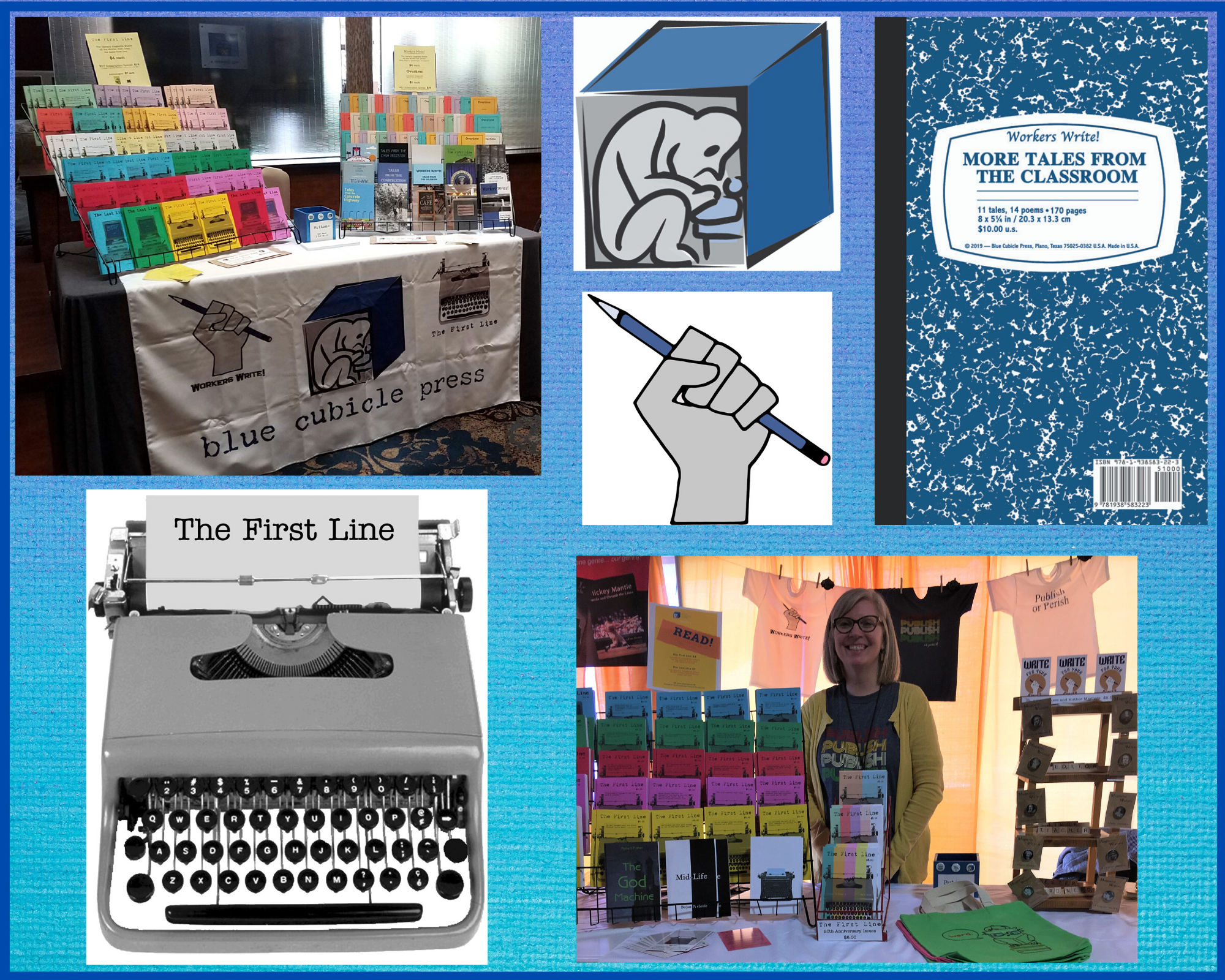

When I met you and your wife, Robin, at the Texas Book Festival last fall, it was clear that The First Line is a team effort. How did Robin get involved?

Robin has been involved with The First Line since day one. She came up with our first first line.

How do you come up with the first lines?

Most are created by the editors (in fact, all of the 2020 first lines are Robin’s). Robin and I write down ten to twenty good first lines each. Then we mix them up and battle over what we think will be the most inspiring. Every two or three years we hold a contest where we have people submit possible first lines.

Why do you think first lines are so important?

As a writer, it’s the ink that defeats the blank page. For me, it’s amazing how easy a story flows, once I have the starter.

As a reader, the first line gives you a sense of what’s to follow – good or bad. Usually the entire book – tone, voice, sometimes plot – can be found in the starter sentence.

As an editor who has been reading stories that begin with the same first line for years, it’s actually the second sentence that grabs my attention. The direction the writer is going in is found in that second sentence.

Share with our readers a little bit about what happens behind the scenes of The First Line. How many submissions do you get per issue? What would cause a story or poem to be rejected?

We receive anywhere from four hundred to six hundred submissions per issue, depending on the sentence, and we publish about forty stories a year (and four nonfiction essays about favorite first lines).

Unlike other literary journals, the premise of The First Line is to write your story starting with the first line as it is given, and it can’t be altered in any way. If a writer alters the starter sentence, these submissions are the first ones to end up in the rejection pile. Call me Ishmael is not the same as “Call me, Ishmael.” Also, poorly edited stories reflect writers who aren’t committed to being published authors. Edit twice, submit once.

My sentiments exactly. Aside from errors, what grabs your attention in a short story?

When all of our submissions begin with the same first line, it’s oftentimes difficult to read without preconceived notions. So, we are overly attuned to the power of the second sentence, and whether or not it flows seamlessly from the first. But what really grabs our attention is the absence of internal criticism. If we are deep in a story and we find ourselves not reading as editors, that’s when we know we have something special.

Let’s talk shop. I think it’s fabulous (and a rarity) that you don’t charge a fee for a writer to submit a story and even sweeter, you pay those writers who get published. How does that work? What are upcoming prompts and deadlines?

We pay on publication: $25.00 - $50.00 for fiction, $5.00 - $10.00 for poetry, and $25.00 for nonfiction (all U.S. dollars). We also send you a copy of the issue in which your piece appears. As for upcoming prompts and submission deadlines:

Summer:

The door was locked.

Due date: May 1, 2020

Fall:

The Simmons public library was a melting pot of the haves and have-nots, a mixture of homeless people and the wealthy older residents of the nearby neighborhood.

Due date: August 1, 2020

Winter:

Loud music filled the room, making it hard to hear anything else.

Due date: November 1, 2020

Blue Cubicle Press, which you and your wife co-own, publishes The First Line, but what else can you tell us about it?

Over the years, we realized that most of the writers we were working with had regular jobs and they knew the dream of making it big as a writer probably wasn’t going to happen, but that didn’t mean they wanted to give up telling stories. We want to hear those stories. Alongside The First Line, we also publish Workers Write!, a yearly anthology that focuses on working-based stories where work is a central part of the plot but not the overwhelming main point. These stories record what work was/is like but are also, hopefully, entertaining. Then, sometimes we receive stories that don’t fit in to the job categories we’ve chosen for WW!, so we created Overtime, a standalone chapbook, that has blossomed into its own publication. The First Line is our first born, but the press has become a collection of working class literature, a sort of curator of the history of work. We’re pretty proud of that. As for the name, I was stuck in a blue cubicle, writing stories during my downtimes, so it seemed appropriate.

Blue Cubicle publishes TFL, Workers Write!, and Overtime. Anything else? Can writers submit stand-alone books for publication?

Yes, we do – rarely – publish standalone novels or collections of short stories, but they have to be work-related in nature.

Do you have any advice for prospective contributors?

Write what you want to read. We discourage writers from purchasing a copy of the journal to get a feel for our editorial tastes. Our tastes change, and we try to include stories that are often overlooked by ‘literary’ magazines. We will always want well-written stories, no matter the genre. If you write with honesty and passion, your story will stand out.

What’s next for y’all? Any more branching out? Changing directions? Other projects?

We’re going to AWP (Association of Writers conference) March 4-7, in San Antonio, and we just started the first edit on The First Line 22.1, and it should be back from the printers in mid-March. And, we’re bringing back The Last Line this year.

Finally, since you’re an editor, I just can’t resist asking… Team Oxford comma?

Team Oxford comma, definitely. And one space after a period (though Robin still insists on two). :-)

A recovering playwright, David LaBounty has been publishing other people’s words since 1999. He is the editor of The First Line, Workers Write! and Overtime. His own work has appeared in magazines and newspapers and on stages across the country. He and his wife, high school librarian Robin, are co-owners of Blue Cubicle Press.