"Texas has been fortunate to have a great number of admirable writers, and if a budding writer grows up in Texas, he or she has had the good fortune to live in a great incubator."

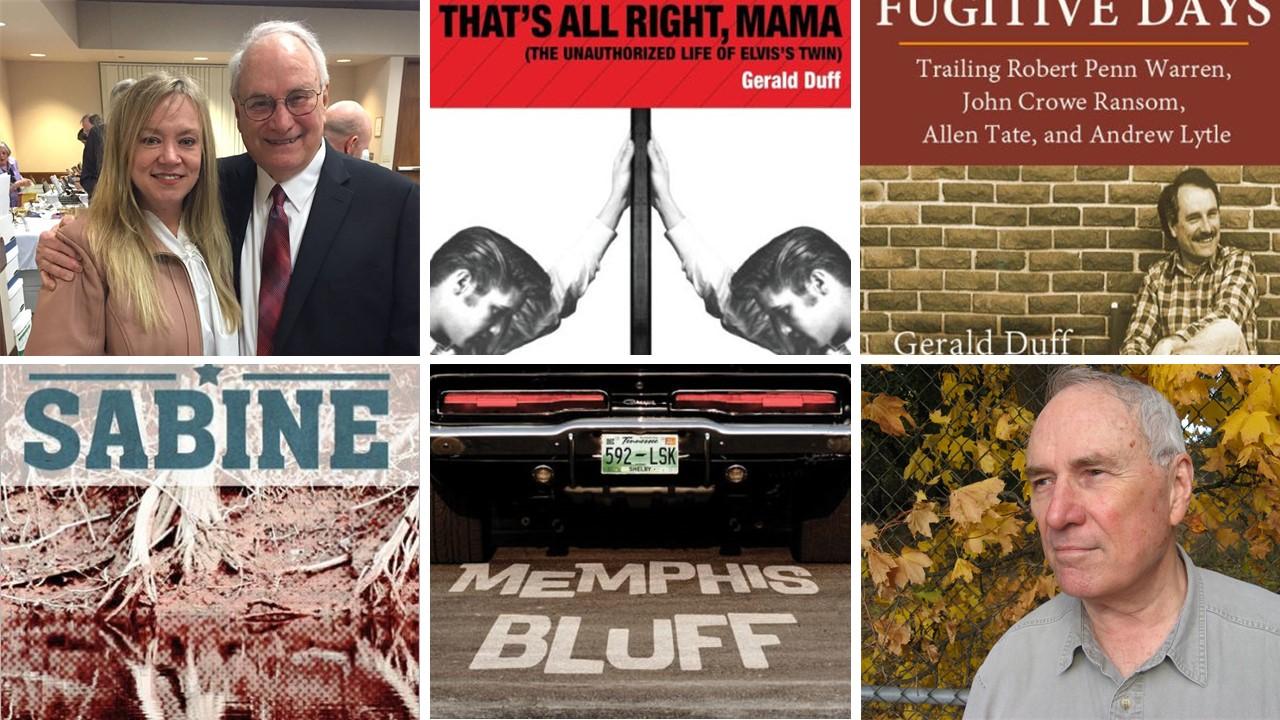

LONE STAR LITERARY LIFE: Mr. Duff, your latest book is Memphis Bluff (Texas Christian University Press, May 2020). Please tell us about your new book.

GERALD DUFF: Memphis Bluff is the third novel in my series set in that feverish city on the Mississippi River. It follows Memphis Ribs and, most immediately, Memphis Luck, all of these being hard-boiled mysteries involving two police detectives in the Central Station of the Memphis Police department.

Memphis Bluff is the latest book in a series starring Memphis cops J. W. Ragsdale and Tyrone Walker, which began with Memphis Ribs (Lamar University Press, 2014). Please tell us about your original inspiration for this series. How is the Memphis setting essential to the stories you want to tell?

I had not intended to write a series when I began the first one, based on a man from Mississippi I’d met when I was living in Memphis, a cotton farmer who’d served in Vietnam, was completely at ease with himself and those around him, who was unafraid and good-natured and world-weary. I based the character of J. W. Ragsdale, my fictional police sergeant, who had given up farming to come to Memphis and sort out crime and evil doers in that city, on this acquaintance. His partner turned out to be an African American man named Tyrone Walker, a lifelong resident of the city, ex-star athlete, happily married man with children, and a good brake on Ragsdale when necessary.

After I’d written that first novel, one tinged with humor and mayhem and some of the flavor of Memphis—that place of great music, beautiful women, prejudice, scores of churches and bars and honky-tonks, and a dark and tormented past—I’d come to like Ragsdale and Walker so much that I kept writing and thinking about them. As I lived in Memphis, listened to its music, observed its rough and ready and awful and yet charming atmosphere, I became intrigued by its character. Booze, blues, and barbecue offered me material, tone, humor, and the hardcore realities of that place. As I’ve written elsewhere, if Nashville, Tennessee, is about making money and taking financial and cultural advantage, its competitor Memphis is about kicking back and having a good time and letting the low-side drag.

You are a prolific writer, Mr. Duff; I count something on the order of twenty books, including novels, short stories, poetry, and a memoir, among other forms. Did you always know you wanted to write? What is the most useful advice you’ve received during your writing career? Was there a teacher in your formative years who played a pivotal role in your development?

I grew up loving to read, particularly fiction, and by the time I started college, I had come to the conclusion that I’d like to write fiction like the books and magazines I’d been reading. I wasn’t focused well at that time, thinking that college was simply where I’d learn to make money to buy stuff, and it wasn’t until I’d taken an English literature survey course at Lamar University in Beaumont that I realized I’d never be an engineer. I’d much rather read more books and maybe try to write.

The best advice I received about trying to write came from several teachers I’d had, both in Nederland High School and Lamar, all saying that anything written could be changed and improved. It just took work, not simply inspiration. Work and imagination lived joined together, and lightning did not have to strike. Sitting down and working, revising, being patient—these components were what mattered most. I remember one teacher repeating advice he’d once heard, “Not inspiration, but perspiration.”

Home Truths: A Deep East Texas Memory (TCU Press, 2011) is your memoir about growing up in the piney woods, overcoming poverty, bigotry, and ignorance to forge your own place. How did an ambitious, book-loving boy manage?

I was lucky enough to have a mother and father who, though poor, loved to read and talk about what they’d read. It became natural to me, that escape from brute reality that one’s imagination allows. It seems to be cliché, but it was true for me, at least, that blotting out what the facts of poverty and backwoods culture presented to me on a daily basis could be achieved and was rewarding emotionally—books, books, books. Years later, when I read Richard Wright’s autobiographical account of his life as an African American child in Mississippi, I realized the universality of the freeing power of the imagination.

The great majority of your work is set in the American South, which has nurtured the greatest of our regional literature, in my opinion. The American South is also a remarkably violent culture, and this seems to also be a through line in your work. Is violence something you consciously decided to examine, or is it something in the air and water—inescapable? At the same time, humor is inextricably twinned with violence in your writing. What are you trying to reconcile or exorcise?

Yes, whether it’s work by Faulkner, Walker Percy, Lee Smith, Katherine Ann Porter, or Ralph Ellison, the fictional accounts of violence and prejudice and cruelty in the South loom large and merge together. If a writer of fiction ignores that reality, the power of the work suffers. I can’t ignore it in my fiction, but I don’t celebrate it.

One way to do that is through cold and serious denouncement. Another is through facing it but using another strong trait in Southern and American character and fiction: humor and satire. That is most effective and emotionally satisfying for me as a writer of fiction. Most people don’t read fiction to be seriously lectured to. They want to be entertained, but the writer’s job is also to slip things by the reader. I think most of the humor in my Memphis novels attempts to defuse and not celebrate or relish violence.

I read a work of criticism several years ago called The Christ-Haunted Landscape: Faith and Doubt in Southern Fiction (University Press of Mississippi, 1994) by Susan Ketchin, in which she spoke with a dozen Southern writers about the influence of religion on their work. What role does religion play in your work? Do you think religion mitigates the violence, or is it part and parcel—or something else entirely? Is it possible to separate the two?

I was brought up in the Southern Baptist tradition. My grandfather was a preacher, and so were—and are—uncles and cousins. So much of that background was poured into me that I fled from it early on. Yet when I read my own novels and short stories, after they’ve been cooled off a bit by the passage of time, I recognize events and characters that are inescapably linked to religious themes and concerns.

But I also have attacked such themes in novels, such as an early one of mine, Graveyard Working. I’m torn. And I believe that religion can warp and twist. Yet many people who I admire and respect are quite religious. They are believers, and they are good people. That makes me nervous. I’m not that way. Why aren’t they like me? How can they be so dumb? Are they dumb? Hmmm.

You have been a college dean and English professor. Have you formed a philosophy for teaching writing? Is it possible to teach creativity?

I don’t think it’s possible to teach talent, but it’s possible to teach understanding and encourage study and attention. One of the best things I heard along these lines came from remarks I heard a high-powered lawyer make at a book signing in Washington, D.C. when he was introducing an old teacher of his who was about to talk about a literary production. “When I was in this man’s English class, he made me worry about why William Wordsworth wrote a certain poem in a certain way. He made me think it was crucially important for me to understand that. He fooled me into thinking that was truly relevant to me and my education. He fooled me. And I’ll thank him for that until the day I die.”

As far as teaching creativity, I don’t think it’s possible. Is it possible to teach understanding of how a writer makes a certain way of expression effective? Yes, it is. I’ve seen it done!

Since this is Lone Star Lit, I always ask what Texas means to a writer and their work. How has the Lone Star State shaped your writing and career? Which Texas writers do you admire?

Texas has been fortunate to have a great number of admirable writers, and if a budding writer grows up in Texas, he or she has had the good fortune to live in a great incubator. Texas is huge, literally and figuratively, and that size has an effect emotionally and culturally on a writer. The state is filled with contradictions, and opposing forces make for energy and drive, which any writer must have.

Texas is heavily materialistic yet devoted to myth and imagination and lies and impossibilities. It can be cruel culturally, yet it is welcoming and celebratory of differences and mixed definitions of self. Texas fools itself often, and that’s the trick writers must learn. Texas writers I admire include Katherine Ann Porter, Horton Foote, John Graves, Larry McMurtry, (and can we claim the Texas based novels of Cormac McCarthy?) [Editor’s note: Yes, yes we can.], Ann Weisgarber, Beverly Lowry, Steve Harrigan, Rod Davis—I could go on!

Can you tell us what’s next for you and your work?

I’m working on an imagined history of the participation by my Duff ancestors (some real, some invented to serve a purpose, like all works of fiction) in American wars. The first, James from Scotland, was defeated at Culloden and expelled from Britain to the English Colony in America, where he was victorious at King’s Mountain in the American Revolution. The second was defeated at Chickamauga in the Civil War; the third was victorious at the Battle of the Bulge in WWII; the fourth defeated in Vietnam; and the fifth killed in Afghanistan. It’s a cheerful prospect!

What books are on your nightstand?

Larry McMurtry’s travel book Roads, Steve Harrigan’s new history of Texas, Chester Himes’s novel Cotton Comes to Harlem, Lee Smith’s memoir Dimestore, and four or five stacked up New Yorkers and the same number of New York Review of Books

Gerald Duff won the 2012 award for the best book of fiction about Texas, Blue Sabine, from the Philosophical Society of Texas; the Cohen Prize for Fiction from Ploughshares magazine; the silver medal from the Independent Publishers Association; and a finalist designation for the Western Writers of America’s Spur Award for 2015. He is a member of the Texas Institute of Letters and the Texas Literary Hall of Fame.