"Most often on the Llano Estacado, there was too little rain and too many weevils but, through force of will, the people of the South Plains coerced the land to yield the largest cotton crops in the nation. This is where I learned character, the value of hard work, and honesty."

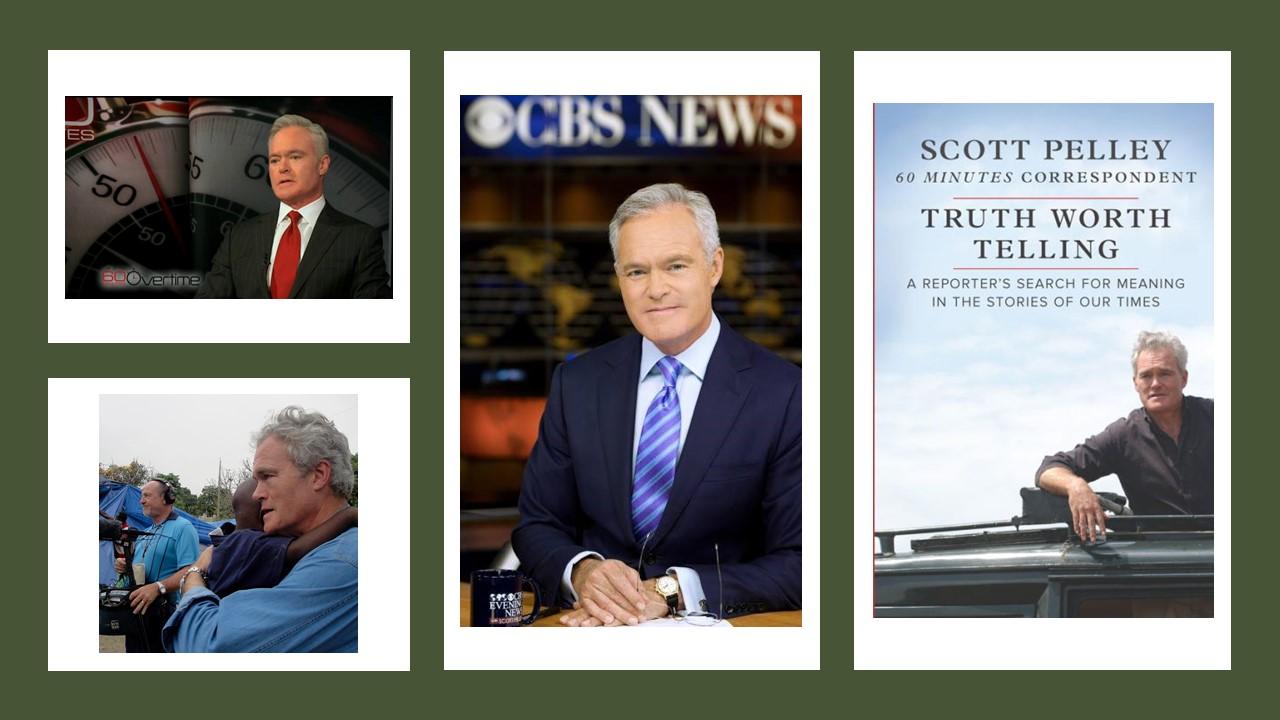

Lone Star Literary Life: Mr. Pelley, you’ve worked in broadcast journalism for more than forty years, and your first book was published this year, Truth Worth Telling: A Reporter’s Search for Meaning in the Stories of Our Times. Please tell us about your book.

Scott Pelley: I wanted to write a memoir, but I didn’t want to write a memoir about me. Over the decades, I have met the most interesting people in the world who discovered the meaning of their lives during historic times. Those were the people I wanted to write about. The book is an anthology of short stories, each about a person or a moment that changed the course of America. The chapters are titled after virtues and fallibilities. For example, the first chapter, entitled “Gallantry,” is about the heroic sacrifice of the Fire Department of the City of New York that I witnessed at the World Trade Center on 9/11. I wrote the book now simply because I couldn’t stop myself. The events I experienced were bursting to get out. I threw open my laptop and laid down one word at a time until there were 130,000 of them.

LSLL: Truth Worth Telling riffs on a quote from an essay you wrote after the November 2015 ISIS attack on Paris: “In these times, don’t ask the meaning of life. Life is asking, What’s the meaning of you.” So, what is the meaning of you?

SP: There is no Democracy without journalism. The founders gave We the People the power over government, but the only way we can exercise that power is with accurate, independent information. In my career, I have strived to do what the founders expected of a free press—seek justice, expose corruption, and give voice to the voiceless.

LSLL: I read recently that you said there would be no Scott Pelley without Texas. What did you mean?

SP: I was born to parents who had grown up in the Oklahoma Dust Bowl. They struggled through the great depression and fought World War II. My dad, John Pelley, signed up for the Army Air Forces the minute he graduated from high school. He flew thirty-five missions over Germany. My mother, Wanda Pelley, built airplanes for the war effort. These were people who taught perseverance, optimism, and resiliency by example. The same was true for their friends and others I knew in Lubbock. Most often on the Llano Estacado, there was too little rain and too many weevils but, through force of will, the people of the South Plains coerced the land to yield the largest cotton crops in the nation. This is where I learned character, the value of hard work, and honesty.

LSLL: Please tell us about your process for writing Truth Wort Telling. Specifically, there are countless evocative, seemingly small details that time and again bring home the core of whatever subject you’re writing about—I’m thinking of those abandoned high heels in Manhattan on September 11, 2001. How do you know which details are going to be important? Is that what you meant when you wrote that Peter Bluff taught you the difference between looking and seeing?

SP: John McPhee, the Pulitzer Prize winning author and Princeton journalism professor likes to say, “A thousand details make one impression.” I tell journalism students that human beings are terrible observers. We tend to overlook the telling details in a person or in a scene. The writer must see more than his reader sees, otherwise, what’s the point in writing? This was what Peter Bluff taught me in a Baghdad bazaar—to take in the texture, the sounds, scents, and images that paint a picture.

LSLL: You quote James Madison as having said that free speech and a free press are “the only effectual guardian of every other right.” And in chapter nine, about Duty and the lessons of war, you write, “The only independent source of information, the check on a government that is advocating war, is the reporter and photographer on the front line.” During the first Gulf War you came to understand the “risk to democracy when the government stands in the way of honest reporting.” How did you learn that lesson?

SP: In the 1991 Gulf War, the Pentagon blocked independent, timely reporting from the battlefield. I was a member of a combat correspondent pool. We were not permitted to transmit our stories from the field even though the technology allowed it. The Pentagon insisted on taking custody of our videotapes and hand-carrying them for distribution at its media center in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia. Few of our stories reached our Dhahran bureaus. The Pentagon held up independent reporting while it told the story it wanted to tell in a daily news conference from a luxury hotel hundreds of miles from the battlefield.

At one stage in the invasion, my military escort wandered several yards away. An army major who found me and my crew “unescorted” put a gun to my head. Apparently, in his view, an American reporter posed the same threat as an enemy combatant. When America goes to war, all of America must go. The way all of America goes to war is through the independent reporting of war correspondents on the battlefield. War is not the administration’s business, it is the people’s business. War will be waged with the sons, daughters, and treasure of the people. When independent reporting is blocked, the people no longer rule.

LSLL: Regarding the last question, the 2019 World Press Freedom Index compiled by Reporters Without Borders (RWB) ranks the United States as forty-eight out of 180 countries and now qualifies as “problematic.” Is RWB justified in their ranking?

SP: When I was managing editor of the CBS Evening News in President Trump’s first year, we were frank about when the president was telling the truth, when he was lying, and how we knew the difference. This led Mr. Trump to call CBS News, “The enemy of the American people.” A few weeks later, I met with Mr. Trump at the White House and told him that I worried some poor deranged individual would shoot up a local newspaper or TV station because it represented the “enemy of the American people.” Mr. Trump thought for a moment and told me, “I don’t worry about that.” Months later, an FBI agent warned me that a man who had mailed a dozen bombs to people he considered opponents of the president, had a file on me in his computer with my home address.

Someone came up to me on the street recently and said, “This must be a terrible time to be a reporter.” “No!” I replied, “This is a great time to be a reporter, because the American people are watching us. This is an opportunity to show them what we do, how we do it, and what our values are.” People who stand to lose from honest reporting will always attack the media. This is what James Madison understood when he created the independent press as a check on the power of government. He understood that as long as Americans could say what we want to say, write what we want to write, and read what we want to read, then all our rights will be protected.

LSLL: In the chapter on Hubris, “Trump v. Clinton,” you write about “fake news” and that “the Constitution of the United States rests in the National Archives in a bombproof vault, but the Russians got to it anyway.” Based on your research and reporting, what is “fake news” and how do we protect ourselves from it?

SP: Fake news is fiction posing as journalism. In Truth Worth Telling I tell the story of a fake online newspaper. It published the story of a small Texas town that was cordoned off by the military because of an outbreak of Ebola virus. There was no outbreak, no military quarantine, the story was complete fiction, but it was viewed one million times. Why create a fictional news site? Because the charlatan behind it made advertising money every time someone clicked on one of his stories. And, he explained to me, the more outrageous the story, the more clicks it drew.

America’s adversaries, including the Russians and Chinese, use the same tactics to influence public opinion. I tell audiences that they have a responsibility to be skeptical and carefully choose credible information. Fortunately, that has never been easier than it is today. When a reader finds something “outrageous” he or she should check with other “brand name” sources they find credible. What did the Dallas Morning News report on this story? What did CBS News or the Wall Street Journal report? These brand-name sources have reputational risk. Their sacred credibility can be ruined if they get a story wrong. You can bet they are working like hell to get it right.

Our 2020 election is already being attacked by disinformation. It will be safe only if the American people do the work to check what they are hearing against real, professional journalism.

LSLL: In a “Field Note” called “Eyes of the Beholders” you write that “when we hit the balance just right, we get double the outrage.” Please explain the phenomenon.

SP: We hear a great deal about bias in the media. I believe, most often, the bias is in the reader and viewer. When I did the first interview with President Elect George W. Bush in 2000, half of our viewer mail castigated me for being too harsh and argumentative, the other half scolded me for going soft on Mr. Bush. Reactions to many stories are informed not by bias in the reporting but in the honestly and passionately held opinions of our viewers.

LSLL: If you could change one decision in your reporting career, what would it be? And which decision would you call again?

SP: In early 2003, when the Bush administration was convincing the American people that war with Iraq was imperative, I interviewed a former Iraqi army chief of staff who had been exiled by Saddam Hussein. The general told me flatly there was no nuclear program nor a program to manufacture chemical weapons. This man had every reason to benefit from an American invasion, and yet he knocked down two of the pillars of the Bush administration’s argument. We reported what the general said on 60 Minutes. But now I realize I should have dropped everything and dug in on Saddam’s alleged weapons of mass destruction. The American people, and reporters in particular, should be at their most skeptical when an administration is bent on war.

As for a decision I would make again, I’m reminded of numbers of times we did not report a story on the CBS Evening News because we could not verify it with our own sources. Too often news organizations simply pass along the reporting of others. Several times we avoided erroneous stories reported by our competitors because we insisted on having our own sources.

LSLL: Which novels inspire you and what books are on your nightstand this evening?

SP: I frequently return to The Grapes of Wrath and Leaves of Grass particularly when I am trying to get my mind warmed up for writing. Recently my nightstand has been occupied by Seeds of Empire, a richly detailed history of cotton and slavery in 19th century Texas. I am also working my way through the series The Story of Civilization by Will and Ariel Durant. A few weeks ago, I was walking on my Texas ranch and I began to marvel at the vibrancy and diversity of life around me. How did all this begin? That question led me to What is Life? How Chemistry Becomes Biology, a fascinating book by Addy Pross, on the science behind the origin of life.

Scott Pelley has been a reporter and photographer for more than forty-five years. He is best known for his twenty years (and counting) on the CBS News magazine 60 Minutes and as anchor and managing editor of the CBS Evening News. Pelley's work has been recognized with three duPont-Columbia Awards, three Peabody Awards, and thirty-seven national Emmy Awards bestowed by the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences. Pelley is the most awarded correspondent in the fifty-one-year history of 60 Minutes.

Pelley has been married to the love of his life for thirty-five years. They have two children. Visit him online here.