Read everything because you never know where you’ll find something you need to know.

Lone Star Literary Life: Ms. Furman, this year is the hundredth anniversary of the O. Henry Prize. You have been the series editor (until very recently—that’s my next question) of the O. Henry Prize Stories, published annually by Anchor Books, since 2002. Please tell us about that experience and what a hundred years of the prizes means to you.

Laura Furman: Being series editor of the O. Henry Prize Stories was wonderful—my best job, really. When I started to do it, I was still teaching at the University of Texas at Austin, and I’ve had the good fortune even after retirement of having wonderful graduate students in writing to help me. In a way, it’s been my finest hour as a teacher because I was able to help my graduate assistants read in a whole new way. Workshops can get you into an auto-repair mind—“We can fix this!” But reading for the O. Henry means that nothing in the story can be changed, and that from the first sentence the writing has to be superb and the story deeply engaging.

When I started as series editor, I changed some of the O. Henry’s procedures—I chose the twenty prize stories, not a committee of jurors. Then I sent the stories to the jurors, who didn’t know who the author was or which magazine had published the story. It was a more level playing field and made it more fun for the jurors because each was on her own, and no one had to wrangle with making a common decision.

Being series editor gave me the chance to honor many writers who weren’t well known but had written a terrific story. Putting the work of new writers in the O. Henry gave the story a bigger and longer life than only appearing in a magazine, crucial and rewarding as that is. The writers were the joy of the job and also the knowledge that all of us were participating in an American literary tradition that was important both to writers and readers.

LSLL: I read just this week in Publishers Weekly that you have moved on as editor of the O. Henry series and joined Randolph Lundine Manuscript Consultants. Did the hundredth anniversary of the prizes seem a fitting time to move on, or is that coincidence? Please tell us about your plans at Lundine.

LF: As the hundredth edition approached, I considered my own life as a writer and knew that I needed much more time to write. The opportunity to work with Ladette Randolph and Heather Lundine came along at just the right time. I’ll be editing manuscripts, which is very different from my work for the O. Henry. It’s different also from being involved with the production of a book each year.

Since I dropped out of college for a year, I’ve worked in publishing houses, as an editor for an arts foundation, and for individual writers. Becoming a consulting editor with Randolph Lundine feels both like a change and a continuation of work I love. Since finishing the O. Henry 2019, I’ve been writing with a new happiness and new energy. It helps, of course, that I finally finished a novel and can return to writing stories.

LSLL: You are the founder of the original iteration of American Short Fiction, along with the Texas Center for Writers and “The Sound of Writing” broadcast on National Public Radio, at the University of Texas Press. I believe this was 1991. The very first issue included Joyce Carol Oates and Dagoberto Gilb. What was your inspiration for founding a literary journal, and how did the project come together?

LF: I founded American Short Fiction with the enormous help of my late friend Susan Williamson and with the blessing and support of James Michener. “The Sound of Writing” came on board later. The head of UT Press then was Jack Kyle, and he was instrumental in starting the journal. I wanted the journal to pay writers for their work, and American Short Fiction did. I’m not one hundred percent sure of the chronology, but at some point Susan and I were joined by Catherine Vanhentenryck and John Zuern. American Short Fiction was recognized by the National Magazine Awards right away, and that gave me great satisfaction.

LSLL: In your opinion, which journals are currently publishing the most innovative work? Which journals do you recommend today? What advice to you have for writers who are considering submitting their work to literary journals? What did you look for as an editor?

LF: I admire a number of journals, and it’s a landscape that changes. Tin House is only online now, for example. Editors leave and the tastes change. I like Southern Review, New England Review, Paris Review, Zzyzyva, Zoetrope—I could go on. I would suggest that writers take a look at magazines before sending in work, not to find work exactly like their own but to see if there’s a sympathetic sense of taste and what’s important in fiction. Every editor is different; I looked for beauty in language and in the form of the story.

LSLL: You also taught for many years at UT Austin. What is your most important advice to aspiring writers?

LF: I’d suggest trying very hard to think less about the future and more about the present. All that will ever matter is your writing. ‘To thine own self be true’—a writer’s integrity and honesty shine through. And read! Not just the latest novelty or most popular fiction but the classics. Read everything because you never know where you’ll find something you need to know.

LSLL: Your first published story appeared in the New Yorker in 1976, which is quite the venue for your first publication. Since then your stories have appeared in many publications, and you have published novels, a memoir, and story collections. How and why did you begin writing?

LF: I started to write because I needed to understand the life I and those around me were living. That’s still true.

LSLL: Personally, short stories are my favorite literary form; I think it requires the same sort of talent as a painter of miniatures. The evocative economy required is astonishing to me. Much of your career seems devoted to short fiction. Is it also your favored form? If so, why, and if not, what is your favorite form and why?

LF: I too love the short story, and the past years of reading for the O. Henry have made me like it even more. Stories are difficult to write because they require, for me at least, patience and kindness, that is, not forcing anything on the page. And they also require from a writer a willingness to go where the story is going, as opposed to where you want it to develop or end. I don’t always, and sometimes never, know what my own stories are about. Interpretation comes much later, if ever.

LSLL: Since this is Lone Star Lit, I always ask what Texas means to writers and their work. You came to Texas from New York; how do you think your work is different than it would’ve been had you remained in the Empire State?

LF: In 1978 I moved to Houston from a farmhouse in upstate New York. I had a few friends in Houston from my days working there for the Menil Foundation. I met my husband, and we’ve lived in Houston, Galveston, Dallas, Lockhart, and Austin. My husband worked for McDonald Observatory for a long time, giving me a chance to see West Texas.

If I’d stayed in New York City, my world would have been smaller in big ways and small, like saying ‘good morning’ as you pass someone in the street or the lobby of a building. And my work? I don’t know. Maybe I wouldn’t have learned to notice the way I did because I was in a new place.

LSLL: Which Texas writers do you admire and why?

LF: There are so many good writers from Texas past and present. One of the first Texas writers I read was Bryan Woolley; his beautiful novel Some Sweet Day is a painful book in many ways and miraculous because it shows wounding and healing. Katherine Anne Porter was one of the best short story writers ever. “Pale Horse, Pale Rider” is a masterpiece of storytelling, heartbreaking without being sentimental. June Arnold’s novel Baby Houston is a gem. The writers closest to me now, as friends and readers, are Michael Parker (Prairie Fever is his latest novel) and Oscar Cásares (Where We Come From).

LSLL: What books are on your nightstand?

LF: I have one big blue book on my nightstand, Horizon by Barry Lopez. I first read him when I published a wonderful story of his about orchards in American Short Fiction.

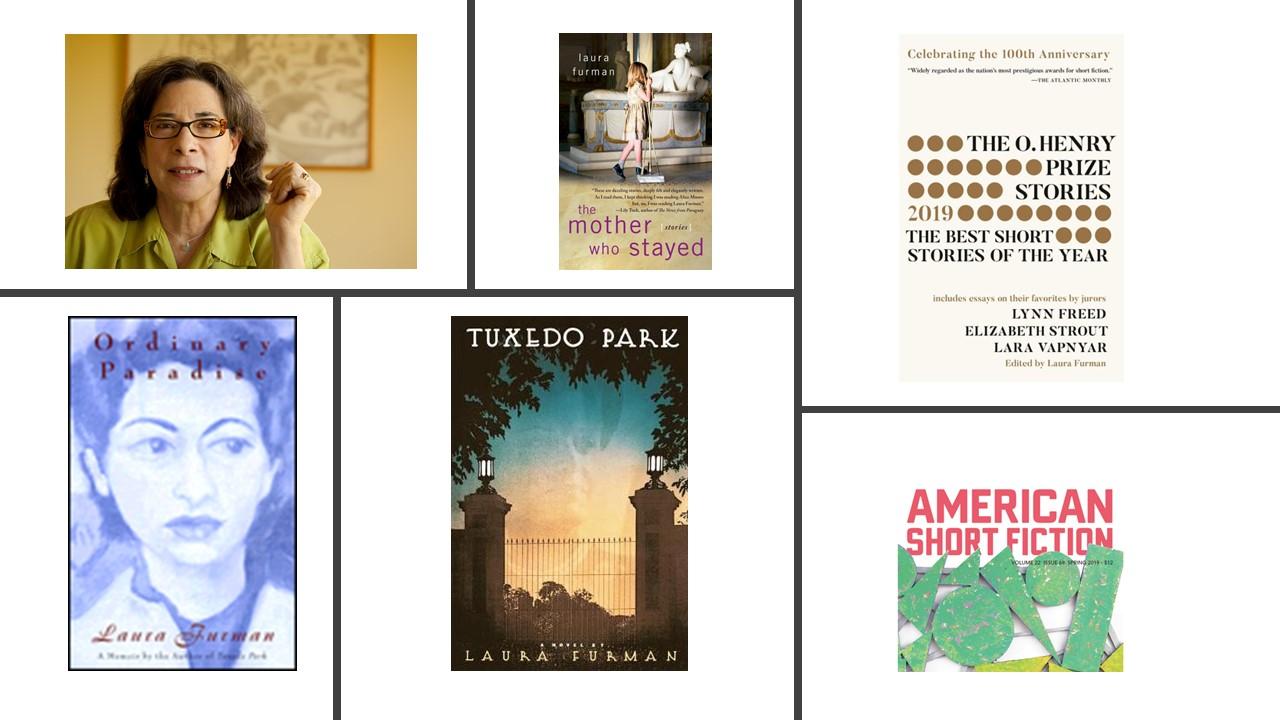

Laura Furman was born in Brooklyn, New York, and graduated from Bennington College. After college she worked at Grove Press and then as a freelance copy editor for various New York publishing houses and the Menil Foundation.

Her first story appeared in the New Yorker in 1976, and since then her work has appeared in Yale Review, Epoch, Southwest Review, Ploughshares, American Scholar, and other magazines. Her books include three collections of short stories, two novels, and a memoir. Her most recent collection is The Mother Who Stayed. Furman's received fellowships from the New York State Council on the Arts, Dobie Paisano Project, the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Arts.

Since 2002, she's been series editor of the O. Henry Prize Stories, published annually by Anchor Books. Each year she selects the twenty winning stories and writes an introduction. For many years, she taught at the University of Texas at Austin, where she is now professor emerita. Furman lives in Austin. Visit her online here.