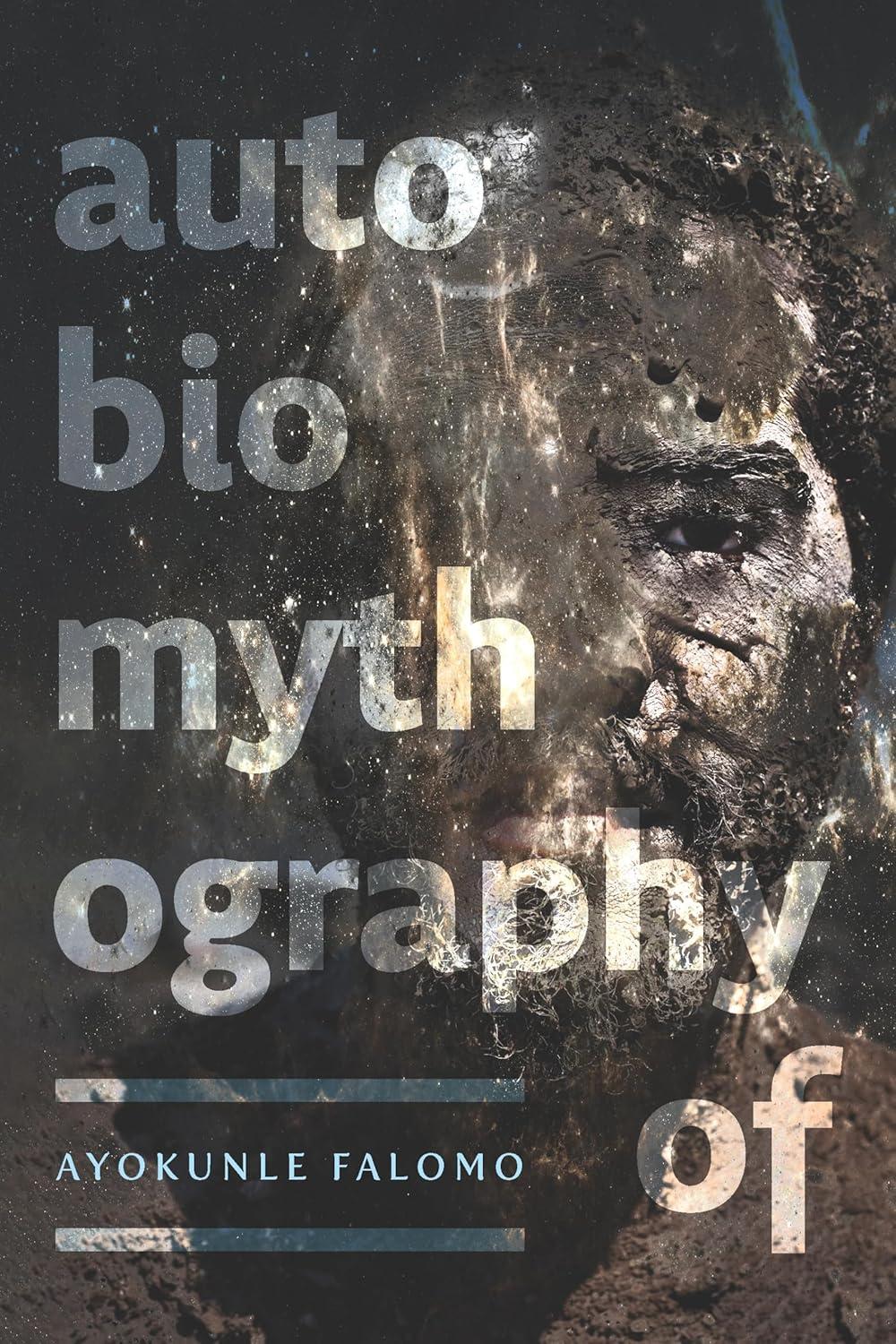

POETRY

Ayokunle Falomo

Alice James Books

September 10, 2024

ISBN-10: 1949944654

This poetry collection is as ambitious as it is rewarding for the reader. Ayokunle Falomo weaves a narrative tapestry of mythos and remembrance, interiority and external reflection, self and other, colonial and native, in a dialectical fabric of poetic inquiry with a compelling reach for clarity. Falomo’s plangent hall of mirrors refracts perception and reality for both the reader and the poet, shaping meanings to be examined in the binary of otherness. The beauty is, you’re never done with this collection: questions asked, re-examined, then reconsidered is an accretive, learning experience, poem by poem; page by page.

Falomo’s poesy evokes the brilliance of Nobel Laureate Derek Walcott’s Omeros, an epic re-mythologizing of Homer as a smooth, polished vehicle to travel an introspective odyssey that inscribes Caribbean identity and history. The composite effect mirrors Robert Johnson’s clever Middle Passage: myth blends with history and discovery. Falomo lures the reader in, then challenges you to find your way out, navigating paired oppositions.

There are forty-five compositions of varying voice and format. Some are poetry in prose, some verse, others iconic narrative formulations that create an overall context for composite imagery sketched over a hundred pages. They interlock, but each can also stand alone. Either way, the poetry is lush, complex, and challenging.

The term “autobiomythography” is Falomo’s first clue to the secret decoder ring: literary theorist Kenneth Burke proposes that mythos—and by extension, Falomo’s clever “autobiomythos”—provides the tracings from which a new and perfect history can be drawn. The “bio” aspect of Falomo’s mythos points to a reimagined self as well as a historical dynamic by which that self must be judged. It’s mythopoeia with a message.

Start on page seventy-four, an intimate self-portrait of the poet (“If Found”), then rewind to page seventy-two to for a sense of how this voice came into being and exists from an émigré’s perspective: it’s autobiographical (sound familiar?) and spoken in disparate tongues (colonial English literally over native Nigerian), also a familiar thematic pattern: are they the same? Equal? Lost? Surpassed? Restored? You decide.

Such disparate poetic voices speak forcefully but consistently smoothly, engendering a gospel choir call-and-response, with various speakers peering into the reflecting pool and offering clashing juxtapositions for the reader to weigh and sort. But Falomo doesn’t just hand over the meaning. In fact, there’s a whiff of Loki-like mischief in the poetic stream. For example, from “Farther:”

In the legend, (the one I dreamed—or

Did I make it up…?) a fatherless boy sleeps

On the bank of a shallow stream with a rock as his pillow. When he wakes up, he walks

Down an endless street, begging for water.

That is preceded by a clever epistolary series from father to unborn child, at once embracing and excoriating the world into which a life is brought into existence. An intertwined boldness and timidity, anticipation and reluctance, plays out over seven, fourteen, and twenty-eight weeks of an unborn parenthood, struggling into a hectic, seemingly indifferent “stovetop world.” And that paternal piety ricochets off “Nigeria Speaks,” the scolding voice of a fatherland abandoned:

… what right do you have to tell anyone about my wrongs? … [do] you have any space left in your heart for shame, or guilt, for leaving me? Do you even remember how to get to your father’s house, eyes closed, without a map?

Diaspora embraced; diaspora scorned; birth and rebirth. Falomo’s is what the maverick Pre-Raphaelite poets would have labeled “powerful song.” Autobiomythography Of is a rich and rewarding journey, one to be savored and not to be missed.

Chris Manno earned his PhD in English from Texas Christian University where he teaches writing.