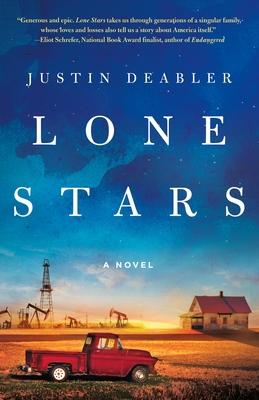

LITERARY FICTION

Justin Deabler

St. Martin’s Press

Hardcover (also available as an e-book), 978-1-2502-5610-2, 304 pgs. $26.99

February 2, 2021

Who remembers the episode of Everybody Loves Raymond in which Marie stands to interrupt when the priest asks if anyone objects to Robert and Amy’s wedding? Later, when Ray stands to give the best-man’s toast, he talks about editing memories, advising Robert and Amy to “just keep the good ones.” Which stories do we choose to tell—not only to others but to ourselves? How do we edit those stories? Most importantly, how do we remember them? Ray’s speech was beautiful, but he didn’t get it quite right; we shouldn’t just keep the good memories because we can learn from the bad ones to make a better future.

Lacy Adams grew up in McAllen with the secrets surrounding her mother’s origins, “a woman who spent her life in hiding, naming the weaknesses of others,” imbibing racism and misogyny. As soon as she’s able, Lacy flees to a graduate science program at UT Austin. Aaron grew up in Midland, a class-conscious striver, embarrassed by his laborer dad, and a football star, dazzled by oil money. Aaron’s flight is diverted to Southeast Asia, downed in the Vietnam War. Julian grew up gay in suburban Houston, “the rhinestone buckle of the Bible Belt,” with his parents, Aaron and Lacy, and all their discontents. He will fly to Boston, to Harvard University, at his first opportunity, with a “chip snuggled comfortably … onto his shoulder.”

Lone Stars is the debut novel from native-Houstonian Justin Deabler. This is a modern family saga, a historical sweep from 1950s South Texas, through the Houston suburbs of the 1980s and ’90s, to contemporary New York City. Lone Stars is an ambitious debut, tackling our most contentious social conflicts to tell a macro tale through the microcosm of one family’s story. There are many kinds of closets in Lone Stars—gendered, sexual, racial, religious, social, intellectual, political, philosophical. Even if you find the courage to emerge, there are still the masks to consider.

Deabler sets a smooth, steady pace that manages to never bog down, though he covers vast territory. Part 1 is told through the limited third-person narratives of Lacy and Aaron, moving from childhood through the early years of their marriage and Julian’s childhood; Julian’s voice joins the narrative in Part 2 in all his prepubescent turmoil. Julian will later tell his groom-to-be, Philip, that he has “. . . this anger inside me that I think could save the world, or some part of it. Or it could burn me up first. I don’t know.” Contradictions abound: Julian “thought of straight people and the pass they got for bad behavior. Their strip clubs, Hooters, Mardi Gras tits for beads—sex so comically bankrupt it left him scratching his head, but if it ends with a few shrieking kids down the road, all is forgiven, right?”

Typically.

The characters of Lone Stars are complex and haunted, recognizable to Texans everywhere; the conflicts they endure, both internal and external, are felt for Texans, from the corrupt land grabs of South Texas to the Christian crusades of megachurches to the greed and cynicism of the Enron debacle.

While parts of Lone Stars are soap operatic, it is immersive and more often a delight, sometimes a revelation. Deabler is a conductor of emotion: the loneliness of swimming against the current; the relief and exhilaration of escape; the despair of betrayal; the wonder of discovery; the tender awkwardness of first love; the peace and comfort of mature love. As Julian says to Philip on their first date, “Every time the world says to us, That’s your defect, we say, No, that’s my strength. My X-ray goggles. And now I see.”

Lone Stars tells a universal story, as all good books do. Each of us spends a lifetime searching for belonging, for our place and our tribe. The best of us, the Lacys of the world, attempt to prepare the ground, amending the soil for the next generation. As Lacy would say, “Raise hell. Never shut up. It’s all over before you know it.”

Justin Deabler grew up in Houston. He dropped out of high school when he was fifteen, went to Simon's Rock College, and graduated from Harvard Law School. He is general counsel for the Queens Public Library. He lives in Brooklyn with his husband, son, and two cats. Lone Stars is his first novel.