“God’s preferential concern for the poor and oppressed,” Beck writes, “runs through the whole of scripture.”

Richard Beck, a psychology professor at Abilene Christian University, leads a Bible study at a maximum-security prison on Monday nights. That’s how he found himself drawn to the theology of legendary country music star Johnny Cash’s songs.

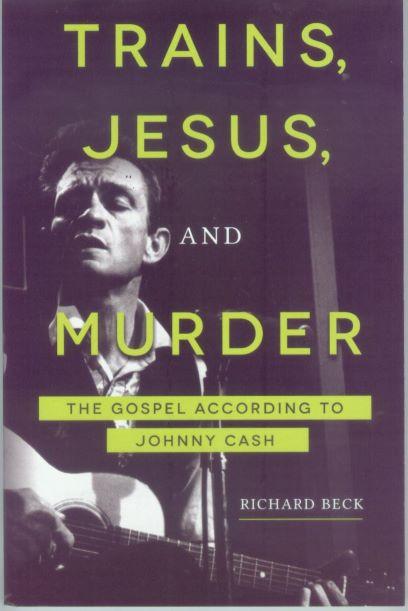

Now he has written a book about it, Trains, Jesus, and Murder: The Gospel According to Johnny Cash (Fortress Press, $18.99 paperback). “Saints and sinners all jumbled together,” Beck writes. “That’s the genius of Johnny Cash, and that’s what the gospel is all about.”

“The music of the Man in Black,” he adds, “gives people the power to comprehend just how deep and wide is God’s love for them.”

Beck divides the book into four sections — Family and Faith; Sinners and Solidarity; Nation and Nostalgia; Suffering and Salvation — and each chapter takes its theme from the title of one of Cash’s songs.

A chapter headed “I Walk the Line” deals with Cash’s failure to be faithful to his wife and family and to God, and how he became addicted to amphetamines and was on the brink of suicide. Yet, Beck writes, “in the pit of hell, grace found Johnny Cash.”

“The gospel,” says Beck, “isn’t about our faithfulness to God; it’s about God’s faithfulness to us.”

The sad song “Give My Love to Rose” headlines a chapter that is essentially about acts of kindness, about caring personally for “the outcast, the downtrodden, and the broken.” Quite a number of other Cash songs showed his solidarity with the oppressed, including “Folsom Prison Blues,” “San Quentin,” “The Man in Black,” and “The Ballad of Ira Hayes.”

“God’s preferential concern for the poor and oppressed,” Beck writes, “runs through the whole of scripture.” And through Johnny Cash’s music as well.

On a personal note, I met Johnny Cash in 1965 at an unauthorized concert in Bryan. His scheduled concert at Texas A&M was cancelled by President Earl Rudder after Cash was arrested for illegal possession of pills in El Paso. I was editor of The Battalion, the A&M student newspaper, and played a role in bringing him to an off-campus nightclub despite the administration’s objections. The Statler Brothers opened, and Cash dedicated a song, “Dirty Old Egg-Sucking Dog,” to Rudder. I was invited to his trailer after the concert, and I’m pretty sure he was high on something. But I have been a fan ever since. See Rob Clark’s book Live from Aggieland for the complete story.

Beck’s book on Johnny Cash is one of several titles published this year dealing with popular music icons, including these with Texas roots:

Janis: Her Life and Music about Janis Joplin, by Holly George-Warren (Simon & Schuster, 400 pages, $28.99 hardcover).

The Messenger: The Songwriting Legacy of Ray Wylie Hubbard by Brian T. Atkinson (Texas A&M University Press, 260 pages, $28 hardcover).

Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan by Alan Paul and Andy Aledort (St. Martin’s Press, 365 pages, $29.99 hardcover).

Contact Glenn Dromgoole at g.dromgoole@suddenlink.net.