"Just sit down, write a sentence, polish it, think about it, then write another sentence. After a while, you’ll have a composition. . . . Writing is mostly rewriting. There are no shortcuts."

It's not hyperbole to call Gary Cartwright a living legend among Texas writers. For five decades he chronicled the stories and personalities of the Lone Star State. From the rough-and-tumble world of police beat and sports reporter in 1950s and ’60s Fort Worth and Dallas to long-form journalism in a new kind of magazine in the ’70s—Texas Monthly. He mastered a diversity of writing approaches, including novels, true crime, and screenplays.

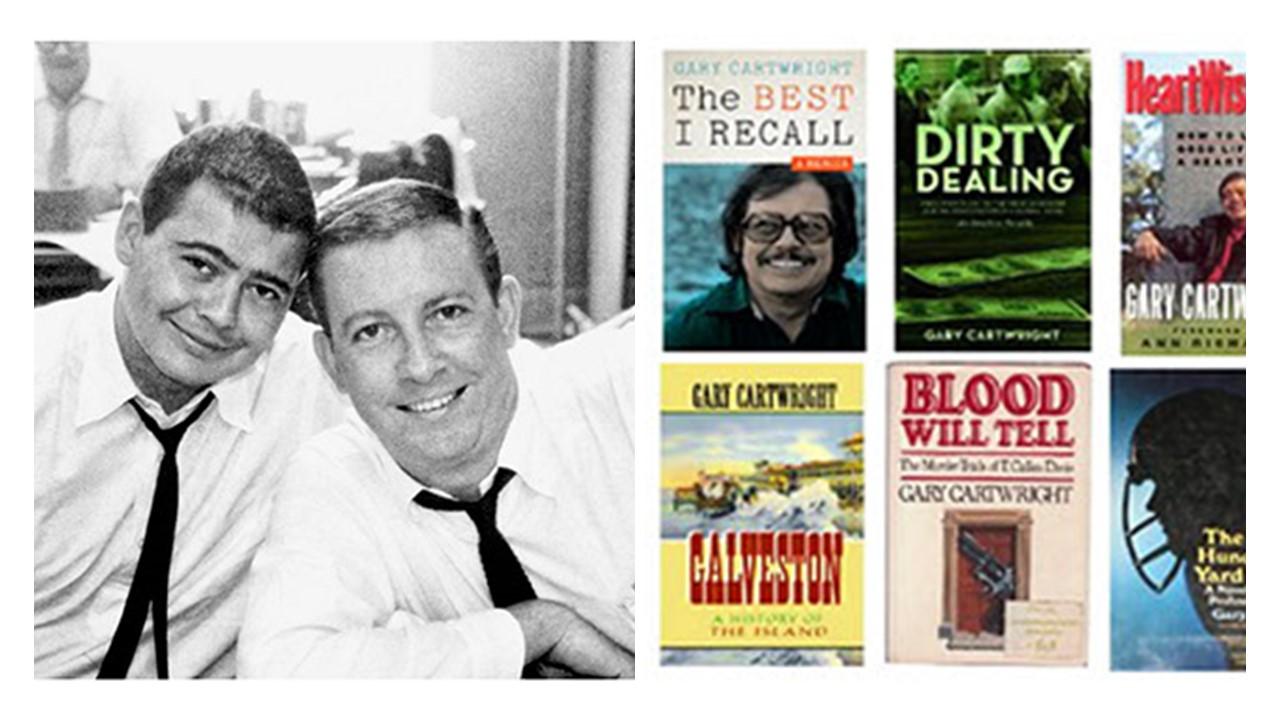

His latest authorship endeavor is his memoir The Best I Recall (University of Texas Press, 2015), and after meeting Cartwright last Saturday afternoon at Scholz’s Garten in Austin, we posted interview questions to him via email.

LONE STAR LITERARY LIFE:Welcome, Gary. In reading your memoir it seems you’ve mastered every form of writing—sports journalism, magazine expose, fiction, screenplays, to name a few. When did you know that you wanted to write?

GARY CARTWRIGHT: I got the idea that I wanted to write in a high school English class taught by my favorite teacher, Miss Emma Ousley, at Arlington High School about 1950. Miss Ousley started every class by having her students write in a notebook. She didn’t care what they wrote and made clear it wasn’t for a grade. Most of the students hated this exercise, but for me it was the best part of the school day. I was like a wild pony galloping free, words spraying out in all directions. I never dreamed anyone would actually read this garbage, but one day Miss Ousley pulled me aside and told me that I had a talent for writing. Nobody had ever told me that I had talent, and I began to think of writing in a new way.

As you began to write, who influenced you?

I read almost everything Hemingway wrote. Also J. D. Salinger, Steinbeck, Victor Hugo, and, later, John LeCarré. I learned to write by imitating the styles of such writers until I developed my own voice.

Some would say that Blackie Sherrod, Dan Jenkins, Bud Shrake, and Gary Cartwright created the best sportswriting team ever. Who do you like writing sports today?

I don’t have a favorite sports writer among today’s crowd. Most of the really good ones write for Sports Illustrated or other national magazines. I love the new crop of writers at Texas Monthly, especially John Spong, Katy Vine, and David Courtney.

What were the early days of Texas Monthly like? No one had ever covered the state with that kind of speaking truth to power before. But it started on a shoestring. When do you know the magazine was going to make it? Did you ever imagine it would have the kind of impact on the state that it did? Was there something about the times or that era that destined TM to be a success?

Texas Monthly was a dream come true. Writers used to talk about the need for a statewide newspaper or magazine to match up with the abundance of talent homegrown in Texas, but it didn’t happen until the mid-1970s when a plumber’s son named Mike Levy from Dallas used his family money to start Texas Monthly. Until then, it was very difficult to make a living freelancing in Texas, long time between finished manuscript and paycheck.

There was no doubt the magazine was going make it, given the talent and the abundance of untold stories in the state. There were no restrictions on length, so we wrote until we had nothing more to say and let the editors cut to size and space. There were lots of arguments between writers and editors, of course, but that was part of the learning process. It was an exciting time of trial and error, of risk-taking and discovery, of success and failure, and the bonding of a staff of like-minded literary aspirants.

In your long-form crime stories you covered some pretty rough characters. Were you ever personally at risk?

I never felt personally at risk, but maybe I was a couple of times. When I had to go into a tough neighborhood or meet with someone I didn’t know, I made sure I had some backup. My longtime best friend, Bud Shrake, was 6-foot-6, weighted about 225, and was at least physically intimidating. Another large and stable friend was Malcolm McGregor, an El Paso lawyer who shared many of my adventures. With Bud or Malcolm as backup, I never worried.

Tell us about Mad Dog, Inc. Some would say that MDI was Texas’s version of the Beats or the Merry Pranksters. Is that an accurate analogy? Who were the members and how was “membership” attained?

Bud Shrake and I invented Mad Dog on a flight back to Austin from LA in the 1970s. It was supposed to be a sort of literary agency and stable for writers/artists, but was mostly just a long-running joke. We did issue membership cards on which was printed the Mad Dog motto: “Doing Indefinable Services for Mankind” and our credo, “Everything That Is Not Mystery Is Guesswork.” Each new member received a kiss on the cheek, a shot of tequila, and two pesos. We printed a few Mad Dog T-shirts and got a lot of publicity making promises we could never keep. As the founders, Bud and I tapped new members wherever we found them (if we had tequila and pesos handy). I remember the actor Peter Boyle was so moved by his Mad Dog membership that he ruined the next shot of the movie he was making by flashing his card to the camera.

In your memoir you talk about some interesting approaches in trying to snag an interview with Texas’s best-known stripper, Candy Barr. Would you still recommend that strategy to journalists today?

Candy Barr was a special person, a special case. She was something of a legend by then and getting her to agree to an interview was most difficult. I had become friends with a Dallas stripper named Chastity Fox, who knew Candy and convinced her to see me. That was the easy part, as it turned out. The story is about that very strange night I spent with Candy, me trying to interview her and Candy trying to cook dinner and be difficult. It wasn’t the story I had imaged but it turned out okay, a fine example of making the best of what’s there.

In the nineties you had a heart attack, an episode you turned into Heartwise Guy, which was part biography, part health advice. How drastic were the life changes you made after your heart attack?

I made some fairly drastic lifestyle changes after my heart bypass surgery. I lost about forty pounds, began working out regularly at the YMCA gym (I still do), and started eating pasta and salad instead of chicken-fried steak and gravy. I didn’t give up drinking but I cut way back. I stopped smoking, except for an occasional joint. I was eighty on my last birthday and I’m still blowing and going, so I must be doing something right.

What’s the best part of being retired?

The best part of being retired is sleeping as late as I like. Also, no deadlines. I don’t miss writing at all, but if the time comes when I do, I’ll find something new to write about, or revisit something old.

Coming from the iconic Texas wordsmith himself, what advice would you have for aspiring Texas writers?

My only advice to aspiring writers is: don’t talk about it, do it! Just sit down, write a sentence, polish it, think about it, then write another sentence. After a while, you’ll have a composition. Whether it is good or not depends on you, on your talent and how much you want it. Writing is mostly rewriting. There are no shortcuts.

* * * * *

Praise for Gary Cartwright's THE BEST I RECALL

“A crisp, entertaining memoir from a happy man.” —Kirkus

“Told with the same rascally wit, streetwise reportage and conversational prose that made him the gold standard at Texas Monthly for 25 years before he retired in 2010, The Best I Recall is the diary of a man crazy enough to try to write for a living and eventually succeeding.” —Dallas Morning News

“The legendary Texas Monthly staffer’s memoir—which features encounters with iconic Texans such as Don Meredith, Ann Richards, Willie Nelson, and Blackie Sherrod—is every bit as funny and outrageous as fans of his pioneering sport writing and true-crime reporting would expect.” —Texas Monthly

“Nobody has lived a more fascinating life of prowling around in Texas journalism than Gary Cartwright, who along the way became a vital part of it. Simply one of the best damn newspaper and magazine writers who ever turned himself loose on a typing machine. Hop on this book, meet a gang of unforgettable characters, and enjoy the ride.”

—Dan Jenkins, author of His Ownself: A Semi-Memoir

“How can Cartwright have led such a memorable life and remembered it? A great life yarn by a great yarn-spinner.”

—Roy Blount Jr, author of Alphabet Juice

Gary Cartwright (1934-2017) grew up in West Texas and Arlington. He received a B.A. in journalism and government from Texas Christian University in 1957. Cartwright reported for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Fort Worth Press, Dallas Times Herald, and the Dallas Morning News. Cartwright's first book, The Hundred Yard War, was published in 1967, at which point he left newspaper work to become a freelance writer. His work has appeared in The Texas Observer, Esquire, Saturday Review, Rolling Stone, and Texas Monthly. Cartwright has been associated with Texas Monthly magazine since its inception in 1973. A collection of his Texas Monthly articles can be found in his Confessions of a Washed-up Sportswriter. His true-crime books Blood Will Tell and Dirty Dealing began as articles for Texas Monthly.

Among the many honors Cartwright has garnered for his writing are the Texas Institute of Letters' Stanley Walker Award for Journalism for "The Endless Odyssey of Patrick Henry Polk" (Texas Monthly, May 1977) and the Press Club of Dallas Katie Award for Best Magazine News Story for "The Work of the Devil" (Texas Monthly, June 1989). Cartwright has written screenplays in collaboration with Edwin (Bud) Shrake, including J. W. Coop (1972) and Another Pair of Aces (CBS-TV, 1990).

Cartwright died in Austin in 2017 at age 82.