A FICTION

Samantha Mabry

Algonquin Young Readers

Hardcover, 978-1-6162-0666-6, (also available as an e-book and on Audible), 288 pgs., $17.95

October 10, 2017

With the implosion of the cities, Sarah Jac and James become jimadors migrant workers harvesting maguey (also known as the century plant) on the ranches of the Southwestern United States in the not-too-distant future. An environmental cataclysm has devastated the country west of the Mississippi River. In conditions that put the Dust Bowl of the 1930s to shame, maguey, which produces a liquid that, “when distilled, becomes pulque, mescal, or, if you are rich, tequila as clear as a tear,” is one of the few crops still viable. Blueberries are extinct, and people literally go crazy from the heat. The jimadors are at the mercy of the ranch foremen, and a terrible accident sends Sarah Jac and James running for their lives.

The fugitives wash up at the Real Marvelous, a ranch outside Valentine, Texas, which the jimadors believe to be cursed. “There could be something wrong here, in this very dirt,” Sarah Jac thinks, and “all that wrongness might be just about to bubble up, ooze from hacked maguey, or seep skyward through the deep, dry cracks in the ground.” A couple forged in extremity, Sarah Jac and James plan to save enough money to escape to the east, “toward the ocean … and pick fruit off trees and dive into cold breaking waves.” But when one of their cons seems to work too well, Sarah Jac and James must overcome her recklessness and his temptation to survive.

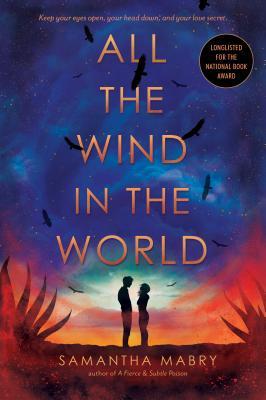

All the Wind in the World, the new novel from Dallas’s Samantha Mabry, has just been longlisted for the 2017 National Book Award in Young People’s Literature. Mabry’s dystopian world, reminiscent of both John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath and Claire Vaye Watkins’s Gold Fame Citrus, is steeped in the native magic of the Southwest. Darkly atmospheric, the climactic conditions inspire superstition—a regression into attempts to appease the gods, seeking a savior and a scapegoat.

Mabry creates complex characters we want to root for, and when they disappoint us the hurt is visceral. Sarah Jac and James, as well as friends and foes, prophets and witches, are no longer children. Forced to grow up too soon, their endurance requires what Sarah Jac calls “hard hearts,” because “desperate people turn, like an apple gone to rot from the inside out.” How to separate caution from paranoia when survival depends upon trust and necessary vulnerability?

“The desert … seems so simple and boring, but really it’s full of secrets,” Sarah Jac tells us. In All the Wind in the World, the desert is a character, and so is the wind, which, “when it hits the right speed, sounds like a string section playing in a minor key.” Dust storms, “hazy, rust-colored curtain[s] extending from the ground to the sky,” roar, and “plow into you, burrow into the folds of your clothing, and stick in the spaces between your teeth.” Mabry’s metaphors sing; her descriptions haunt.

Mabry’s fast-paced plot is straightforward and uncluttered, but packs plenty of twists. The immediacy of Sarah Jac’s first-person narration is powerful and absorbing. The climax is a shocking act of desperation that makes a mostly satisfying ending possible, if only for a very few. As with all things in All the Wind in the World, it’s unsentimental and complicated, and a resonant warning of possible futures without the “luxury of expectations.”

Michelle Newby is a reviewer for Kirkus Reviews and Foreword Reviews, writer, blogger at TexasBookLover.com, member of the Permian Basin Writers' Workshop advisory committee, and a moderator for the Texas Book Festival. Her reviews appear in Pleiades Magazine, Rain Taxi, Concho River Review, Mosaic Literary Magazine, Atticus Review, The Rumpus, PANK Magazine, and The Collagist.