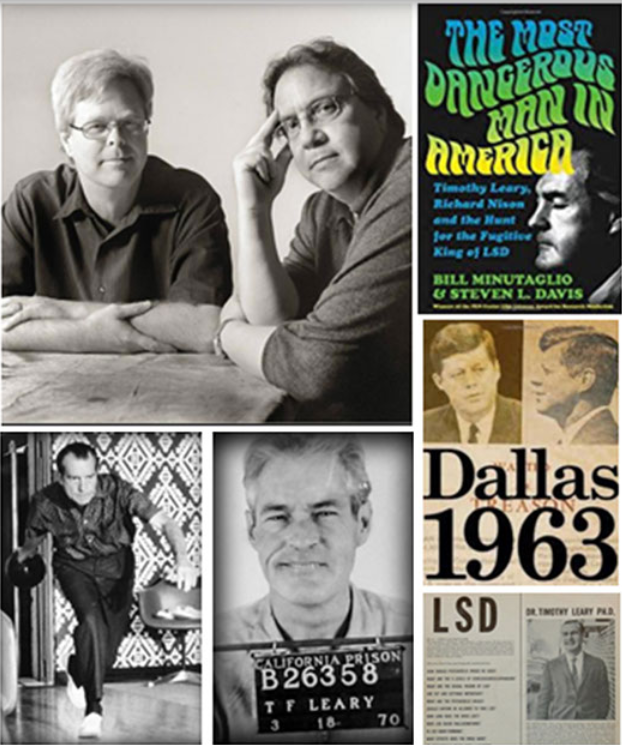

Bill Minutaglio is the author of several nonfiction books. His journalism has appeared in many national and international newspapers and magazines, and his books include Dallas 1963 (Twelve); First Son: George W. Bush and the Bush Family Dynasty (Times Books); City on Fire: The Explosion That Devastated a Texas Town and Ignited a Historic Legal Battle (HarperCollins); The President’s Counselor: The Rise To Power of Alberto Gonzales (HarperCollins); Molly Ivins: A Rebel Life (PublicAffairs); In Search of the Blues: A Writer’s Journey to the Soul of Black Texas (University of Texas Press).

Dallas 1963, co-authored with Steven L. Davis, was the winner of the PEN Center USA national literary award for research nonfiction.

Steven L. Davis is an award-winning author and editor of several books, including J. Frank Dobie: A Liberated Mind and Texas Literary Outlaws: Six Writers in the Sixties and Beyond.

Davis is the current president of the Texas Institute of Letters, a literary honor society founded in 1936 with an elected membership consisting of the state’s most respected writers. He is a longtime curator at the Wittliff Collections at Texas State University, which holds the papers of many major authors.

Collaborating successfully on a writing project takes a special kind of talent —and hefty doses of patience, compromise, and careful time management. Texas writers Bill MinutaglioSteven L. Davis have teamed up for a second nonfiction title from well-regarded publisher Twelve that has garnered critical praise. The authors joined forces as well for an email interview in this week's Lone Star Lit, discussing their separate backgrounds and shared processes in The Most Dangerous Man in America: Timothy Leary, Richard Nixon and the Hunt for the Fugitive King of LSD.

LONE STAR LITERARY LIFE: Bill, you were born in Brooklyn in the mid-1950s and grew up there. As an adult in the late seventies your varied and exciting experiences included earning a graduate degree from Columbia journalism school; interning at the United Nations; being a part of a government food distribution program for poor children in Harlem — and starting off as a beginning reporter for the Abilene Reporter-News. What made you decide to come to Texas, and what was it like adjusting to the Lone Star State?

BILL MINUTAGLIO: I was offered a job at the newspaper in Abilene when I was graduating from journalism school. I had never been west of the Mississippi before and thought it would be a wonderful, important adventure. It was the best decision I ever made, in many ways. I got my New York City ego kicked out of me, and I met so many great people. One of the people at my first newspaper in Abilene had been one of Buddy Holly’s backup singers — how about that! I wound up covering rodeos, goat cook-offs, and a million things I knew nothing about. I learned how much I had to learn. It took me a long time to adjust, and I guess I still am [adjusting]. I love Texas, and every place I’ve lived in.

LSLL: Steve, where did you grow up, and how did it influence your lifelong writing about iconoclasts?

STEVE DAVIS: I grew up on the tail end of the 1960s in a working-class suburb of Dallas regarded as “The Pee Wee Football Capital of the World.” I spent a lot of time cracking heads with other kids on the gridiron. In the classroom, football coaches–posing–as–history teachers preached that noble coonskin-cap wearing Anglo-Americans had marched into the wilderness, vanquished evil enemies, and created a glorious paradise on earth. Well, you know, I believed all that. Never once were we taught to think for ourselves. Once I got to college and figured out we’d been lied to, subjected to low-rent propaganda, I wanted to learn the stories of what really happened. I’ve been on that journey ever since, and honestly, it’s the iconoclasts who’ve shown the way, who have lived the lives I’m interested in.

LSLL: Steve and Bill, how would you each describe the path that brought you to authoring books?

BILL: I used to read the great columnist Jimmy Breslin growing up. And the poetry of Ogden Nash and Langston Hughes when I was in grade school. And it made me want to be a writer. I started in newspapers, veered to magazines, and always dreamed of being an author. It seemed too far away, and at times, it still seems that way.

STEVE: In a word, hardscrabble. I grew up loving to read but never received any encouragement to pursue the literary arts. It took me a long time to figure out that I am a writer. In retrospect the signs were evident early on, but I certainly didn’t recognize them at the time, nor did anyone around me. Once I resolved to be a writer, it took me another twenty years to publish my first book. I had a long apprenticeship, but that’s a good thing, because it taught me to be humble, and to be hungry. I also learned that the best quality for a writer, besides innate intellectual curiosity and an ability to accept constructive criticism, is perseverance.

LSLL: How did you two meet, and when did you first decide to collaborate as co-authors?

BILL: I’ll give my version: I contacted Steve some years ago because I knew his brilliant reputation as a writer and as a scholar of Texas literature. I had accumulated decades worth of papers, documents, drafts of books and articles — and I wondered if Steve might be interested in acquiring them for his archives. He was very, very kind to put up with such a pretentious request — and then more kind to accept the donated papers! Call me gobsmacked. We stayed in touch, developed a mutual appreciation society — there is no finer writer, thinker in Texas than Steve. And, to boot, he is humble — and one of the most generous people I’ve met in the world. He is very giving, very discerning, very thoughtful. He also happens to know so much about so many things — and I’ve learned enormously from him and his equally excellent family. It was pretty easy to decide to collaborate — and I think it might have been steve who first suggested it.

STEVE: I’d known of Bill by reputation as a brilliant writer but didn’t pay much attention, because I’m intrinsically distrustful of the hype machine. Then one day I happened to read an excerpt of his work in an anthology and was blown away — he was one of the best narrative stylists I’ve ever read. At that point I resolved to get to know the man. We quickly became friends and found many things in common to talk about. Bill is one of the most generous-minded and kind-spirited people I know. As we began talking about some of our mutual interests, we both realized that we had done a lot of thinking and reading on Dallas in the early 1960s. We decided to join forces and write Dallas 1963.

LSLL: The title you mentioned, published in 2013, was your first co-authored book. Dallas 1963 was winner of the PEN Center USA Literary Award for Research Nonfiction, was named one of the Top 3 JFK Books by Parade Magazine, and was ranked by The Daily Beast as #1 of the 5 essential Kennedy assassination books ever written. What made this book different from all of the other books on the topic of President Kennedy’s assassination?

BILL: Well, that’s an easy one to answer: the book is not about the assassination. It’s about the days, weeks, months leading up to the awful day in Dallas. It is about a small group of people— heroes and villains — who wrestled over ways to define Dallas, to represent Dallas. We wanted to show what life was like in this city that was doomed to host such an infamous day. And we decided to try something different — to find a small group of people that we could use as a living prism through which we can see the turmoil, hopes, fears, paranoia, empathy, grace, and ugliness. We wanted to tell the real story of Dallas — through the people living there.

STEVE: All the dust kicked up by conspiracy theories has obscured a basic fact of the Kennedy assassination: right after JFK’s death, most Americans blamed Dallas for the president’s murder. Dallas had become a notorious “City of Hate,” the headquarters for an extremist, violent resistance movement to Kennedy. Many of JFK’s friends and advisors warned him to avoid Dallas. And when JFK was preparing to leave for Dallas the morning of November 22 he told Jackie, “We’re heading into nut country today.” So we wanted to tell that story — which had been overlooked for nearly fifty years. As it turned out, our focus on the setting, on the civic leaders in Dallas who violently opposed Kennedy, offered a fresh and revelatory new perspective on the assassination.

LSLL: A collaborators, how would you describe your creative process?

BILL: We would basically decide which people, time periods, events each of us would concentrate on — and research ’em, write ’em up, and then share sections of the books with each other. Kicking it back and forth. I’ve done a ton of collaboration in my career. I co-wrote my first book with my wife. I co-wrote a book with one of my other best friends (Mike Smith, with whom I wrote Molly Ivins: A Rebel Life). I collaborated with another best friend on a book called Locker Room Mojo. And I have had tons of double bylines on various newspaper and magazine stories. I used to be a ‘rewrite man’ at the Dallas Morning News, which meant that I would rewrite stories filed to me by correspondents and reporters — big stories, breaking news stories, about plane crashes, riots and things like that. And I learned long ago that it is never 100 percent a walk in the park. If it was that way, there would be no juice, flavor, and the creative spark that comes from great debate! I have such enormous respect for Steve — his writing is among the finest ever, his research is far better than I could ever achieve, and he has an ability to edit and structure things in the most amazing way. I am beyond lucky to have worked with him, and learned from him.

STEVE: I wish I could lie and say it’s easy. The fact is, both Bill and I are vision-driven, and while we’re often in general agreement on the big things, we do have different visions as to how to get there. We’ve both had to compromise mightily, and we’ve had to rely on our deeper friendship to carry us through the roughest patches of collaborating. But the upside is that we each come at the material from different perspectives, and we’ve gotten awfully good at rewriting each other’s prose back and forth to the point where it’s almost impossible to tell who wrote what (though I can always recognize and admire Bill’s gorgeous wordplay; he is a genius with language). When we put our heads together, the final result often transcends whatever we could have done on our own. In other words, I wouldn’t recommend the process, but I do recommend the results.

LSLL: Almost five years after Dallas 1963, you’re back with The Most Dangerous Man in America. What made you two decide to take on Timothy Leary, Richard Nixon, and 1970?

BILL: I was tired of the doom and gloom — of modern politics, of the way the things we had written about in our first book together, still seemed present today. Divisiveness. Anger. Hate. People yelling at each other. We had kicked around doing a “big book” about New Mexico, Los Alamos, and the creation of the atomic bomb — but publishers were not interested. Not sure why, but I think it had to do with us not finding the right human prisms that we could tell the story through. We had talked a lot about music, about people who run against the tide, who buck the system. I knew I liked writing about people like that. Not sure how Timothy Leary came up, but I know he was on the short list of people I always wanted to explore.

I had met Leary in the early 1980s, and had stayed in touch with him very sporadically over the years. And he seemed incredibly fascinating — and fun — to write about.

Well before we decided to write about him, I had a beautiful photograph hanging on my office wall: it was taken the day I met Leary and we had talked for hours and hours.

So, perhaps, for me, it was fate.

STEVE: As I mentioned earlier, Bill and I are often in agreement on the big things, and we’ve both been interested for years in Dr. Timothy Leary, the counterculture icon and High Priest of LSD. We’ve both been fascinated by this little-known episode in Leary’s life, when he escaped from a California prison in 1970. And it’s not just Leary who’s fascinating, it’s also the times -- this is when the nation seemed to be breaking apart under Nixon’s rule. We understood there was potentially a good book to be done on this episode, and once we learned that the New York Public Library had acquired over six hundred boxes Leary’s extraordinary personal papers, we knew that we’d be able to tell that story.

LSLL: Can you describe The Most Dangerous Man in America for our readers?

BILL: I’m going to let Steve do this — because he is more succinct than I can ever be!

STEVE: This is the real-life account of Dr. Timothy Leary, the ex-Harvard professor and famed LSD guru who had been locked up for ten years in a California prison after being caught with two marijuana cigarettes. Leary had been running against Ronald Reagan for California governor at the time, and his campaign song, written for him by his friend John Lennon, was later recorded by the Beatles as “Come Together.” In September 1970, Leary broke out of prison with the help of the radical Weather Underground (which had been bombing government buildings in protest of the Vietnam War) and then he fled to Algeria, where he was received by Black Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver at the Panther’s opulent embassy. (If this is starting to sound surreal, that’s because the true events of this story are insanely absurd.) Leary became identified as “the Most Dangerous Man in America” by President Richard Nixon, who was himself unraveling and engaging in criminal enterprises, as president, far surpassing any crimes Leary could have dreamed up. Nixon became obsessed with recapturing Leary, and our book follows the twenty-eight-month-long manhunt for Leary.

LSLL: The Most Dangerous Man in America draws on “thousands of freshly available and unexamined primary resources” from multiple countries. What sort of new pieces of information did you uncover?

BILL: My favorite one is one that was hiding in plain sight — and that we chose to open the book with: we came across a secret White House tape that others might have heard, but never really studied or wrote about. It was a tape in which President Nixon basically declares war on Timothy Leary. Decides to make Leary Public Enemy Number One. It was incredible, to me! The way a president can demonize someone, make politics personal. And, in a way, Nixon’s secret decision unleashed what became known as the “War on Drugs” in America — and it set off a very wild, absurd, chain of events that we are still enduring today.

STEVE: We had so many cool resources: archives from Leary, Nixon, Black Panther leaders, the FBI and CIA, declassified State Department telegrams. We were able to listen to Nixon’s secret White House recordings and be in the room with the president and his aides as they strategized how to demonize Leary.

LSLL: Some political pundits have noted similarities between Nixon and the current occupant of the White House. Do you find The Most Dangerous Man in America to have any analogous zeitgeist to 2017?

BILL: I wrote an op-ed that might, or might not, appear in some papers these days. It revolves around the idea of “What if Richard Nixon could tweet?” And the premise is that he would probably be tweeting many of the same things we see being tweeted today! There is, all across politics, this demonization, this sense of making politics personal. And that began, in earnest, under Nixon. There is a kind of hysteria — on the left and right — and that was certainly there back in the days of Nixon and revolution on the streets of America.

STEVE: That’s an excellent question. It’s funny, because we finished writing this book prior to the 2016 election cycle, and so we had no idea how much of what we wrote would turn out to parallel where we are today. There’s a chapter in our book, “Madman” (currently excerpted in LitHub), that describes Richard Nixon acting in ways that made his closest aides fear that he had become mentally unstable. We also see Nixon embracing the “Madman” role — he wanted to make his enemies believe that he was so psychologically erratic, so impulsively violent, that he might launch a nuclear strike in a fit of rage. It seemed like long-ago history when we wrote that, but now it’s more chilling than ever to contemplate that sort of mind inside the White House.

LSLL: What's next for you two? Do you plan to collaborate again?

BILL: I’m older than Steve, slowing down a bit, and right now I’m looking forward to spending more time at our little home on the Llano River. We have a beaver that has created a hideout/lair along the river bank, and the gar fish are back, along with the Guadalupe River bass, and I like going out there to think about a favorite old dog of mine that loved being in that river — I get goose bumps thinking about him running free, diving in the water, practically laughing and doing what he was born to do.

STEVE: It’s been a great run with Bill and we’ve created two books that I’ll always be proud of and hope will stand the test of time. But we’re each our own people, and we each need to get back to doing our own things. And, honestly, my friendship with Bill is more important to me than any books we write together. And I’ll always be the biggest fan of whatever Bill goes on to write. As for me, I’ve been playing around with some ideas for future nonfiction books and am also wrapping up a comic novel set in the Big Bend region of Texas, called “Odd Cactus.”